Ring-tailed lemur

Taxonomy

- Order: Primate

- Suborder: Strepsirrhini

- Infraorder: Lemuriformes

- Superfamily: Lemuridae

- Genus: Lemur

- Species: catta

Ring tailed lemurs are Strepserhines (Streir, 2011). Strepserhines include such primates as Lemurs, Galagos and Lorises. The main characteristic seperateing Haplorhines (Monkeys, Apes and Tarsiers) and Strepserhines is a rhinarium (wet nose). Another charactersitic is the reliance on olfaction. Strepserhines tend to be more reliant on olfaction when compared to Haplorhines. Due to their dependence on olfaction they tend to have longer noses compared to Haplorhines ((Streir, 2011). Ring-tailed lemurs are part of the large group of Lemurs endemic to Madagascar. Approximently 12 species of lemurs are located in Madagascar. They range from 700 to 3800 grams. Lemurs tend to be diurnal, arboreal/semi terrestrial, large troops, female dominance, have a toothcomb, mulitmale groups and matrilineals.

Female dominace is exhibited by most lemur species and involves the ability for the female to consistently evoke submissive behavior from all males (Jolly, 1966; Richard, 1987; Kappeler, 1993). emale dominance can only occur in contexts of male submission (Hrdy, 1981). When males exhibit spontaneous male submission to females in the absence of female aggression, this is termed deference (Kappeler, 1993a). In the absence of male deferential behavior, females can elicit submissive male behavior through the use of aggression (Sauther, 1993).

Female dominace is exhibited by most lemur species and involves the ability for the female to consistently evoke submissive behavior from all males (Jolly, 1966; Richard, 1987; Kappeler, 1993). emale dominance can only occur in contexts of male submission (Hrdy, 1981). When males exhibit spontaneous male submission to females in the absence of female aggression, this is termed deference (Kappeler, 1993a). In the absence of male deferential behavior, females can elicit submissive male behavior through the use of aggression (Sauther, 1993).

Another animal that has shown female dominance is the spotted hyena (Kruuk, 1972; Frank, 1989; Smale et al., 1993). However, they do not exhibit true female dominance, as seen in lemurs, since female hyenas do not consistently dominate males in all contexts (Smale et al., 1993; Frank et al., 1989). Jolly (1966) found most dominance interactions that occur among lemurs occur in the context of feeding and often occur with the female supplanting the males. Female lemurs will have feeding priority after winning aggressive interactions with males who submissively vocalize and retreat (Jolly, 1966, 1967, 1984).Ring-tail lemurs lack sexual dimorphism, both females and males are the same size (Mittermeier et al., 1994; Sussman, 2000).

Another animal that has shown female dominance is the spotted hyena (Kruuk, 1972; Frank, 1989; Smale et al., 1993). However, they do not exhibit true female dominance, as seen in lemurs, since female hyenas do not consistently dominate males in all contexts (Smale et al., 1993; Frank et al., 1989). Jolly (1966) found most dominance interactions that occur among lemurs occur in the context of feeding and often occur with the female supplanting the males. Female lemurs will have feeding priority after winning aggressive interactions with males who submissively vocalize and retreat (Jolly, 1966, 1967, 1984).Ring-tail lemurs lack sexual dimorphism, both females and males are the same size (Mittermeier et al., 1994; Sussman, 2000).

Males have scent glands within their wrist. The scent glands on the wrist have a horny epidermal spine that sticks out from a bare patch of skin on the wrist. They also have scent glands on their chest (just above their collarbone and close to the armpit) and anogenitally. Females only have scent glands located anogenitally. (Mittermeier et al., 1994; Rowe, 1996; Groves, 2001; Palagi et al., 2004).

They tend to be terrestrial and they often move via walking or running quadrupedally and holding their tails vertically (Mittermeier et al., 1994; Jolly, 2003). L.  catta are endemic to southwestern Madagascar (Sussman, 1977). Madagascar is located 800 kilometers from Southeast Africa. It is the fourth largest island in the world (Swindler, 2002). Southern Madagascar is characterized by a rainy season that occurs from November to March (Jolly, 1966). L. catta are mainly found in forests of dry bush, gallery, deciduous, scrub and closed canopy forests (Mittermeier et al., 1994). L. catta are opportunistic omnivores and their diet mainly consists of fruit, leaves, flowers, herbs, other plant parts, and sap (Sauther, 1992; Mittermeier et al., 1994). Sauther (1992) found that 30% to 60% of their diet consisted of feeding on fruit and 30% to 51% of their diet consisted on feeding on leaves and herbs.

catta are endemic to southwestern Madagascar (Sussman, 1977). Madagascar is located 800 kilometers from Southeast Africa. It is the fourth largest island in the world (Swindler, 2002). Southern Madagascar is characterized by a rainy season that occurs from November to March (Jolly, 1966). L. catta are mainly found in forests of dry bush, gallery, deciduous, scrub and closed canopy forests (Mittermeier et al., 1994). L. catta are opportunistic omnivores and their diet mainly consists of fruit, leaves, flowers, herbs, other plant parts, and sap (Sauther, 1992; Mittermeier et al., 1994). Sauther (1992) found that 30% to 60% of their diet consisted of feeding on fruit and 30% to 51% of their diet consisted on feeding on leaves and herbs.

L.  catta live in multi male, multi female groups ranging from nine to twenty two animals but on average have groups of fourteen animals (Sauther, 1991; Sussman, 1991). Females are philopatric and males disperse; dispersing males tend to enter new groups with one or two other males from their original groups (Sauther, 1991; Sussman, 1991). Generally one female is the single highest-ranking female. The highest-ranking female is typically the one to initiate group movement in a certain direction (Jolly, 1966; Sauther and Sussman, 1993). Females form a dominance hierarchy in which certain females will out rank other females depending on the matriline to which they belong; however, every female is more dominant than males. These dominance relations are reinforced by agonistic encounters (Jolly, 1966; Taylor and Sussman, 1985; Gould et al., 1999).

catta live in multi male, multi female groups ranging from nine to twenty two animals but on average have groups of fourteen animals (Sauther, 1991; Sussman, 1991). Females are philopatric and males disperse; dispersing males tend to enter new groups with one or two other males from their original groups (Sauther, 1991; Sussman, 1991). Generally one female is the single highest-ranking female. The highest-ranking female is typically the one to initiate group movement in a certain direction (Jolly, 1966; Sauther and Sussman, 1993). Females form a dominance hierarchy in which certain females will out rank other females depending on the matriline to which they belong; however, every female is more dominant than males. These dominance relations are reinforced by agonistic encounters (Jolly, 1966; Taylor and Sussman, 1985; Gould et al., 1999).

Males within these social groups are peripheral; however, there are often one to three central/dominant males. The male hierarchy is often dependent on age (Sussman, 1992). Generally the central males are more fit than other males, while the lower ranking/peripheral males are older, recently transferred males as well as younger males that have yet to transfer (Sussman, 1991; 1992; Gould, 1996; Gould et al., 1999). The higher-ranking males often have more interactions with females and thus are more likely to mate, but lower-ranking males also mate (Sussman, 1991, 1992; Gould, 1994, 1996; Gould et al., 1999).

Males within these social groups are peripheral; however, there are often one to three central/dominant males. The male hierarchy is often dependent on age (Sussman, 1992). Generally the central males are more fit than other males, while the lower ranking/peripheral males are older, recently transferred males as well as younger males that have yet to transfer (Sussman, 1991; 1992; Gould, 1996; Gould et al., 1999). The higher-ranking males often have more interactions with females and thus are more likely to mate, but lower-ranking males also mate (Sussman, 1991, 1992; Gould, 1994, 1996; Gould et al., 1999).

Females start reproducing when they are two or three years old and generally havean interbirth ratio of 2 to 3 years (Sauther, 1991). Mating activity in a group will normally last for two to three weeks per year (Sauther, 1991), however, each individual female will only be sexually receptive for one to two days per year (Van Horn and Resko, 1977; Sauther, 1991).

Females start reproducing when they are two or three years old and generally havean interbirth ratio of 2 to 3 years (Sauther, 1991). Mating activity in a group will normally last for two to three weeks per year (Sauther, 1991), however, each individual female will only be sexually receptive for one to two days per year (Van Horn and Resko, 1977; Sauther, 1991).

Work Cited/ Read more

Altmann, J. (1974). Observational study of behavior: sampling methods. Behaviour, 49(3), 227.

Frank, L.G.; Glickman, S.E. & Zabel, C.J. (1989). Ontogeny of female dominance in the spotted hyena: Perspectives from nature and captivity. Symposia of the Zoological Society of London 61: 127-146.

Gould, L. (1994). Patterns of affiliative behavior in adult male ring-tailed lemurs (Lemur catta) at the Beza-Mahafaly Reserve, Madagascar, Ph.D. dissertation, Washington University, St. Louis.

Gould L. (1996). Male-female affiliative relationships in naturally occurring ring-tailed lemurs (Lemur catta) at the Beza-Mahafaly Reserve, Madagascar. American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 39(1): 63-78.

Gould L, Sussman RW, Sauther ML. (1999). Natural disasters and primate populations: the effects of a 2-year drought on a naturally occurring population of ring-tailed lemurs (Lemur catta) in southwestern Madagascar. International Journal of Primatology. 20(1): 69-85.

Groves C. (2001). Primate taxonomy. Washington DC: Smithsonian Inst Pr. 350.

Hrdy, S.B. (1981) The woman that never evolved. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA.

Jolly, A. (1966). Lemur behavior: a Madagascar field study. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Jolly, A. (1967). Breeding synchrony in wild Lemur catta. In Social communication among primates (S. A. Altmann, ed.) University of Chicago Press, Chicago, Illinois. pp. 3–14

Jolly, A. (1972). Troop continuity and troop spacing in Propithecus verreauxi and Lemur catta at Berenty (Madagascar). Folia Primatologica 17:335–362.

Jolly, A. (1984). The puzzle of female feeding priority. In Female primates: studies by women primatologists (M. Small, ed.) Alan R. Liss, New York. pp 197–215

Kappeler, P.M. (1993). Female dominance in primates and other mammals. In: Perspectives in Ethology, Volume 10: Behavior and Evolution. Bateson, P.P.G.; Klopfer, P.H. & Thompson, N.S. (eds.), Plenum Press, New York, pp. 143-157.

Kruuk, H. (1972). The spotted hyena: a study of predation and social behavior. University of Chicago Press, Chicago.

Lewis, R. (2010). Grooming patterns in verreaux’s sifaka. American Journal of Primatology, 72(3), 254-261.

Mittermeier RA, Tattersall I, Konstant WR, Meyers DM, Mast RB. (1994). Lemurs of Madagascar. Washington DC: Conservation International. 356.

Pereira, M., Kaufman, R., Kappeler, P., & Overdorff, D. (1990). Female dominance does not characterize all of the lemuridae. Folia Primatologica; International Journal of Primatology, 55(2), 96.

Richard, A.F. (1987) Malagasy prosimians: female dominance. In Smuts, B.B., Cheney, D. L., Seyfarth, R. M., Wrangham, R. W., and Struhsaker, T.T. (eds,), Primate societies. Chicago, University of Chicago Press.

Sauther ML. (1991). Reproductive behavior of free-ranging Lemur catta at Beza Mahafaly Special Reserve, Madagascar. American Journal of Physical Anthropology 84:463–477.

Sauther ML. (1992). Effect of reproductive state, social rank and group size on resource use among free-ranging ring-tailed lemurs (Lemur catta) of Madagascar. Ph.D. dissertation, Washington University, St. Louis, MO.

Sauther, M.L. (1993). Resource competition in wild populations of ring-tailed lemurs (Lemur catta): implications for female dominance. In Lemur Social Systems and Their Ecological Basis. P.M. Kappeler and J.U. Ganzhorn, eds. Plenum Press, New York

Sauther ML, Sussman RW. (1993). A new interpretation of the organization and mating systems of the ring-tailed lemur (Lemur catta). In Lemur social systems and their ecological basis. Kappeler PM, Ganzhorn J, editors. New York: Plenum Press. pp. 11–121.

Smale, L., Frank, L.G. & Holekamp, K.E. (1993). Ontogeny of dominance in free-living spotted hyenas: Juvenile rank relations with adult females and immigrant males. Animal Behaviour 46: 467-477.

Strier, K. (2011). Primate Behavioral Ecology. Upper Saddle River, N.J.: Prentice Hall.

Sussman RW. (1977). Socialization, social structure, and ecology of two sympatric species of Lemur. In Primate biosocial development: biological, social, and ecological determinants. Chevalier-Skolnikoff S, Poirier FE, editors. New York: Garland Publishing. p 515–528.

Sussman RW. (1991). Demography and social organization of free-ranging Lemur catta in the Beza Mahafaly Reserve, Madagascar. American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 84:43–58.

Sussman RW. (1992). Male life history and intergroup mobility among ring-tailed lemurs (Lemur catta). International Journal of Primatology 13:395–413.

Swindler DR. (2002). Primate dentition: an introduction to the teeth of non-human primates. Cambridge ( UK ): Cambridge University Press 284.

Taylor L, Sussman RW. (1985). A preliminary study of kinship and social organization in a semi-free-ranging group of Lemur catta. International Journal of Primatology 6(6): 601-614.

Van Horn RN, Resko JA. (1977). The reproductive cycle of the ring-tailed lemur (Lemur catta): sex steroid levels and sexual receptivity under controlled photoperiods. Endocrinology 101(5): 1579-1586.

White, F. J., Overdorff, D. J., Keith-Lucas, T., Rasmussen, M. A., Kallam, W. and Forward, Z. (2007), Female dominance and feeding priority in a prosimian primate: experimental manipulation of feeding competition. American Journal of Primatology 69: 295–304.

Wright, P. (1999). Lemur traits and Madagascar ecology: Coping with an island environment. American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 110(2), 31-72.

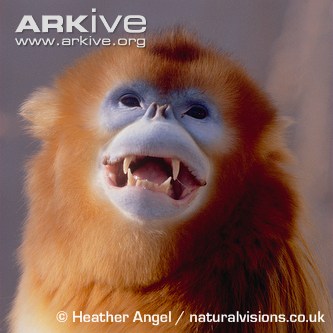

The genus snub-nosed monkeys (Rhinopithecus) consists of 5 species (3 are endemic to China). The golden snub-nosed monkey or Sichuan snub nosed monkey is brightly colored species found in the Sichuan mountains (Liu et al., 2012) Golden snub-nosed monkeys are Old World Monkeys (Catarrhini). Old world monkeys are made up of Colobinae and Cercopithinae. Golden snub-nosed monkeys are part of Colobinae subfamily (Grover, 2001). A group characterized by leaf eating (Liu et al., 2012). The first described snub-nosed monkeys were named by Milne-Edwards in 1870s. Roxellana was a concubine of the Suleiman the Magnificent (Napier, 1970).

The genus snub-nosed monkeys (Rhinopithecus) consists of 5 species (3 are endemic to China). The golden snub-nosed monkey or Sichuan snub nosed monkey is brightly colored species found in the Sichuan mountains (Liu et al., 2012) Golden snub-nosed monkeys are Old World Monkeys (Catarrhini). Old world monkeys are made up of Colobinae and Cercopithinae. Golden snub-nosed monkeys are part of Colobinae subfamily (Grover, 2001). A group characterized by leaf eating (Liu et al., 2012). The first described snub-nosed monkeys were named by Milne-Edwards in 1870s. Roxellana was a concubine of the Suleiman the Magnificent (Napier, 1970). Golden snub-nosed monkeys are brightly colored with a prominent upturned nose. They have flap over their nostrils, a tail shorter than their body (characteristic of old world monkeys). Their body color is yellow with varying tones from brown to bright orange-red. They also have a thick black stripe down their back (Groves, 2001).

Golden snub-nosed monkeys are brightly colored with a prominent upturned nose. They have flap over their nostrils, a tail shorter than their body (characteristic of old world monkeys). Their body color is yellow with varying tones from brown to bright orange-red. They also have a thick black stripe down their back (Groves, 2001). They are located in central and western china (Grover, 2001). They are found in four proveniences of china including the eastern edge of the Qinghai Tibet Plateau and Central China, the Qinling mountains (Shaanixi province), the Minshan mountain (Gansu Province), the Qinghai mountains and Minshan mountains (Sichuan Province) and the Daba mountain (Hubei Province). They are found largely in the Shennongiia forest. Like they panda they are considered a national animal icon (Liu et al., 2012).

They are located in central and western china (Grover, 2001). They are found in four proveniences of china including the eastern edge of the Qinghai Tibet Plateau and Central China, the Qinling mountains (Shaanixi province), the Minshan mountain (Gansu Province), the Qinghai mountains and Minshan mountains (Sichuan Province) and the Daba mountain (Hubei Province). They are found largely in the Shennongiia forest. Like they panda they are considered a national animal icon (Liu et al., 2012). Golden snub-nosed monkeys like other Colobines are primarily arboreal herbivores (Liu et al., 2012). They live at altitudes of 1400-3400 meters. They live in the three types of habitats; mixed evergreen, deciduous broadleaf forests and mixed deciduous and conifer forest. These forests are characterized by winters that lead to food scarcity. They are primarily folivorious but will also eat buds, fruits, barks, lichens and insects and their diet changes seasonally (Li and Jiang, 2010). They mainly eat lichen (43% of the diet) (Liu et al., 2013).

Golden snub-nosed monkeys like other Colobines are primarily arboreal herbivores (Liu et al., 2012). They live at altitudes of 1400-3400 meters. They live in the three types of habitats; mixed evergreen, deciduous broadleaf forests and mixed deciduous and conifer forest. These forests are characterized by winters that lead to food scarcity. They are primarily folivorious but will also eat buds, fruits, barks, lichens and insects and their diet changes seasonally (Li and Jiang, 2010). They mainly eat lichen (43% of the diet) (Liu et al., 2013). Golden snub-nosed monkeys are found in large groups of 50-600 groups (Luo et al., 2014). One subgroup of the larger groups is a one male unit (OMU) which consist of one male and several females with their offspring (Li and Jiang, 2010; Li and Zhoa, 2007). This group system is similar to Gorillas. The second sub group consists of all males (adults and subadults). They are often close in proximity to the OMUs but are not allow mating rights since the males of the one male units monopolize the females (Yoa, 2016; Li and Jiang, 2010). However, females will often move between the OMU and mate with extra unit males (Luo et al., 2014). Extra group males appear to father half of the offspring within the large groups (Yoa, 2016).

Golden snub-nosed monkeys are found in large groups of 50-600 groups (Luo et al., 2014). One subgroup of the larger groups is a one male unit (OMU) which consist of one male and several females with their offspring (Li and Jiang, 2010; Li and Zhoa, 2007). This group system is similar to Gorillas. The second sub group consists of all males (adults and subadults). They are often close in proximity to the OMUs but are not allow mating rights since the males of the one male units monopolize the females (Yoa, 2016; Li and Jiang, 2010). However, females will often move between the OMU and mate with extra unit males (Luo et al., 2014). Extra group males appear to father half of the offspring within the large groups (Yoa, 2016). Golden snub-nosed monkeys breed seasonally. Most births occur during March to May peaking in April. Copulations occur in September and November. They look give birth during this time because of its overlap with spring and the growth of the preferred food season (Li and Zhoa, 2007). Millar (1977) argued this developed in order to fulfill the energetic needs of lactation. Females are pregnant for 6 months (ranging from 193-204 days). Females generally initiates all copulations similar to other Colobines (Western black and white Colobines) (Li an Zhoa, 2007).

Golden snub-nosed monkeys breed seasonally. Most births occur during March to May peaking in April. Copulations occur in September and November. They look give birth during this time because of its overlap with spring and the growth of the preferred food season (Li and Zhoa, 2007). Millar (1977) argued this developed in order to fulfill the energetic needs of lactation. Females are pregnant for 6 months (ranging from 193-204 days). Females generally initiates all copulations similar to other Colobines (Western black and white Colobines) (Li an Zhoa, 2007).

Howler monkeys (Genus: Aloutta) are part of the taxonomic group Platyrrhini (New World Monkeys). They are a subfamily of Atelinae. The Atelinae subfamily are characterized by their large size and their prehensile tail (Di Fiore, 2011; Groves 2001). Aloutta are widely spread in Central and South America.

Howler monkeys (Genus: Aloutta) are part of the taxonomic group Platyrrhini (New World Monkeys). They are a subfamily of Atelinae. The Atelinae subfamily are characterized by their large size and their prehensile tail (Di Fiore, 2011; Groves 2001). Aloutta are widely spread in Central and South America.

Howler monkeys live in several different ecosystems including tropical rainforests, dry deciduous forest, mountain forests, lowland forest and mangroves (Kowalewski et al., 2015). A. palliata live in forest ranging from close canopy ever green forest to deciduous woodlands. A. pigra are considered to be habitat specialists living in undisturbed tropical rainforest (Smith, 1970; Conservation biology of genus Alouatta). Many groups of howler monkeys live within forest fragments surrounding by cattle farms or agricultural area (Cortés-Ortiz et al., 2003).

Howler monkeys live in several different ecosystems including tropical rainforests, dry deciduous forest, mountain forests, lowland forest and mangroves (Kowalewski et al., 2015). A. palliata live in forest ranging from close canopy ever green forest to deciduous woodlands. A. pigra are considered to be habitat specialists living in undisturbed tropical rainforest (Smith, 1970; Conservation biology of genus Alouatta). Many groups of howler monkeys live within forest fragments surrounding by cattle farms or agricultural area (Cortés-Ortiz et al., 2003). Howler monkeys are characterized by their enlarged hyoid bone and their ability to produce distinct loud calls (Baldwin and Baldwin, 1976; Schon, 1986; 1988; Mittermeier et al., 1998). Howler monkeys are part of the Atelidae family and Atelinae subfamily (Di Fiore, 2011). They have one of the loudest primate vocalizations of the Neotropics (da Cuncha et al., 2015). The structure of the hyoid bone is cup like with large hollow air sacs located on either side of the bone (Schönn, 1971). The large hollow air sacs help produce the resonating loud calls (Schönn, 1971; Mittermeier et al., 1998). Like most other neotropic primates they are arboreal (Kowalewski et al., 2015).

Howler monkeys are characterized by their enlarged hyoid bone and their ability to produce distinct loud calls (Baldwin and Baldwin, 1976; Schon, 1986; 1988; Mittermeier et al., 1998). Howler monkeys are part of the Atelidae family and Atelinae subfamily (Di Fiore, 2011). They have one of the loudest primate vocalizations of the Neotropics (da Cuncha et al., 2015). The structure of the hyoid bone is cup like with large hollow air sacs located on either side of the bone (Schönn, 1971). The large hollow air sacs help produce the resonating loud calls (Schönn, 1971; Mittermeier et al., 1998). Like most other neotropic primates they are arboreal (Kowalewski et al., 2015). Howler monkeys live in groups of one to three adult males, several adult females and their offspring. Most species of Aloutta exhibit group sizes of 10-15 individuals with less than three males. This includes A. seniculus, A. carraya, A. guariba, and A. pigra. However, A. palliata (mantled howler monkeys) tend to have large groups with three or more adult males and nine or more females. The largest groups have been reported to be made up of up to forty individuals (Di Fiore, 2011; Chapman 1998).

Howler monkeys live in groups of one to three adult males, several adult females and their offspring. Most species of Aloutta exhibit group sizes of 10-15 individuals with less than three males. This includes A. seniculus, A. carraya, A. guariba, and A. pigra. However, A. palliata (mantled howler monkeys) tend to have large groups with three or more adult males and nine or more females. The largest groups have been reported to be made up of up to forty individuals (Di Fiore, 2011; Chapman 1998). Howler monkeys are generally folivorious but will supplement their diet with fruits (Di Fiore, 2011). Due to their folivorious diets they show adaptions for leave break down. This includes long retention times for digesting within the alimentary canal allowing for gut bacteria to break down the carbohydrates in leave (Di Fiore, 2011).

Howler monkeys are generally folivorious but will supplement their diet with fruits (Di Fiore, 2011). Due to their folivorious diets they show adaptions for leave break down. This includes long retention times for digesting within the alimentary canal allowing for gut bacteria to break down the carbohydrates in leave (Di Fiore, 2011). Overall Howler monkeys rely on slow digestion in order to efficiently extract energy from the leaf carbohydrates. They tend to eat immature leaves since this tend to have a higher ratio of protein and focus on plants with less plant secondary compounds (Di Fiore, 2011). They also tend to show energy minimization, meaning they rest for long periods of time to allow digestions of the leaves (Di Fiore, 2011).

Overall Howler monkeys rely on slow digestion in order to efficiently extract energy from the leaf carbohydrates. They tend to eat immature leaves since this tend to have a higher ratio of protein and focus on plants with less plant secondary compounds (Di Fiore, 2011). They also tend to show energy minimization, meaning they rest for long periods of time to allow digestions of the leaves (Di Fiore, 2011). Generally, both sexes will typically disperse from their natal groups before their first reproduction (Crockett, 1984; Di Fiore, 2011). However, female tends to disperse more often and move a further distance when compared to males (Di Fiore, 2011). Males disperse to attempt to take over a social group from an existing dominant male. Female howler monkeys of A. seniculus are targeted by older females within their natal groups leading to their dispersal. They often have difficulty integrating into existing social groups and will instead form new social groups with other dispersers. The new social group will establish a home range followed closely by breeding (Crockett, 1984; Di Fiore, 2011).

Generally, both sexes will typically disperse from their natal groups before their first reproduction (Crockett, 1984; Di Fiore, 2011). However, female tends to disperse more often and move a further distance when compared to males (Di Fiore, 2011). Males disperse to attempt to take over a social group from an existing dominant male. Female howler monkeys of A. seniculus are targeted by older females within their natal groups leading to their dispersal. They often have difficulty integrating into existing social groups and will instead form new social groups with other dispersers. The new social group will establish a home range followed closely by breeding (Crockett, 1984; Di Fiore, 2011). Howler monkeys exhibit sexual dimorphism with males being larger than females. A. caraya and A. guariba are sexually dichromatic (Kowalewski et al., 2015). Both males and females within the group form dominance hierarchy that are often correlated with age (within A. seniculus and A. palliata). Males are dominant over females and the dominant male tend to have more access to females. Dominant females often exhibit aggression toward subordinate females and their infants (Crockett, 1984; Di Fiore, 2011). Females within Aloutta paliatta exhibit their first reproduction as 4 years of age (Glanders, 1980; Crockett, 1984). Male take overs are often associated with high infant mortality relating to infanticide (40% disappeared infant) (Crockett, 1984). Females within A. seniculus exhibit a sex cycle of 26 days and 2-3 days of estrus. They gestate approximately for 191 days (Delfer, 2004). Several species exhibit tongue flicking prior to mating (Delfer, 2004)

Howler monkeys exhibit sexual dimorphism with males being larger than females. A. caraya and A. guariba are sexually dichromatic (Kowalewski et al., 2015). Both males and females within the group form dominance hierarchy that are often correlated with age (within A. seniculus and A. palliata). Males are dominant over females and the dominant male tend to have more access to females. Dominant females often exhibit aggression toward subordinate females and their infants (Crockett, 1984; Di Fiore, 2011). Females within Aloutta paliatta exhibit their first reproduction as 4 years of age (Glanders, 1980; Crockett, 1984). Male take overs are often associated with high infant mortality relating to infanticide (40% disappeared infant) (Crockett, 1984). Females within A. seniculus exhibit a sex cycle of 26 days and 2-3 days of estrus. They gestate approximately for 191 days (Delfer, 2004). Several species exhibit tongue flicking prior to mating (Delfer, 2004)

Gorillas are found within Gabon, the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), the Republic of the Congo, Equatorial Guinea, the Central African Republic, Cameroon, Rwanda, and Uganda (Robbins et al., 2001). Gorillas are part of the taxonomic family of Pongidae (Great Apes). Groves (1970) split gorillas into three subspecies: western lowland gorilla (Gorilla gorilla gorilla), eastern lowland gorilla (Gorilla gorilla graueri) and mountain gorillas (Gorilla gorilla beringei).

Gorillas are found within Gabon, the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), the Republic of the Congo, Equatorial Guinea, the Central African Republic, Cameroon, Rwanda, and Uganda (Robbins et al., 2001). Gorillas are part of the taxonomic family of Pongidae (Great Apes). Groves (1970) split gorillas into three subspecies: western lowland gorilla (Gorilla gorilla gorilla), eastern lowland gorilla (Gorilla gorilla graueri) and mountain gorillas (Gorilla gorilla beringei). Although all of the gorilla’s subspecies are folivorious they exhibit differences in diet diversity (Taylor et al., 2003). Mountain gorillas tend to be more folivorious when compared to eastern and lowland gorillas. Western lowland gorillas tend to feed on fruits and insects along with leaves. Eastern lowland gorillas are seasonally frugivores (Yamagiwa et al., 1994; 1996; Kuroda et al., 1996; Robbins et al., 2001). Mountain gorillas lack fruit in their diet because of their high elevation locations. They tend to live at elevations of approximately 4000 meters (Robbins et al., 2001).

Although all of the gorilla’s subspecies are folivorious they exhibit differences in diet diversity (Taylor et al., 2003). Mountain gorillas tend to be more folivorious when compared to eastern and lowland gorillas. Western lowland gorillas tend to feed on fruits and insects along with leaves. Eastern lowland gorillas are seasonally frugivores (Yamagiwa et al., 1994; 1996; Kuroda et al., 1996; Robbins et al., 2001). Mountain gorillas lack fruit in their diet because of their high elevation locations. They tend to live at elevations of approximately 4000 meters (Robbins et al., 2001).

Western lowland gorillas are widely distributed and have a population of 110,000 gorillas (Robbins et al., 2001; Harcourt, 1996). They are located in Gabon, the DRC, the Central African Republic, the Republic of Congo, and Equatorial Guinea (Harcourt, 1996). Eastern lowland gorillas are mostly located in the DRC and have a population of 17,000 individuals (Harcourt, 1996; Robbins et al., 2001). Mountain Gorillas have two different geographic populations. The first population is located in the Virunga Mountains in Rwanda, Uganda and the DRC. The second population is located in Bwindi Impenetrable National Park in Uganda. They are made up of 600 individuals, 300 located in each area (Robbins et al., 2001).

Western lowland gorillas are widely distributed and have a population of 110,000 gorillas (Robbins et al., 2001; Harcourt, 1996). They are located in Gabon, the DRC, the Central African Republic, the Republic of Congo, and Equatorial Guinea (Harcourt, 1996). Eastern lowland gorillas are mostly located in the DRC and have a population of 17,000 individuals (Harcourt, 1996; Robbins et al., 2001). Mountain Gorillas have two different geographic populations. The first population is located in the Virunga Mountains in Rwanda, Uganda and the DRC. The second population is located in Bwindi Impenetrable National Park in Uganda. They are made up of 600 individuals, 300 located in each area (Robbins et al., 2001). The gorilla genus was fully recognized by Geoffrey in 1853 (Groves, 2001). Western gorillas (Gorilla gorilla gorilla) are documented as having relatively small teeth and larger incisors when compared with eastern gorillas. They also have shorter hair, brown gray to reddish crowns, flared nostrils, and adult males have a characteristic light gray back and thighs (Groves, 2001). Eastern gorillas (Gorilla beringei) are described as having small incisors when compared to western gorillas. They have longer hair specifically on their brows, tend to be jet black and exhibit gray white back only. They also have narrower nostrils. Mountain gorillas (Gorilla beringei beringei) are described as being quite large with a strongly flared jaw. They are shaggier and have angular nostrils (Groves, 2001).

The gorilla genus was fully recognized by Geoffrey in 1853 (Groves, 2001). Western gorillas (Gorilla gorilla gorilla) are documented as having relatively small teeth and larger incisors when compared with eastern gorillas. They also have shorter hair, brown gray to reddish crowns, flared nostrils, and adult males have a characteristic light gray back and thighs (Groves, 2001). Eastern gorillas (Gorilla beringei) are described as having small incisors when compared to western gorillas. They have longer hair specifically on their brows, tend to be jet black and exhibit gray white back only. They also have narrower nostrils. Mountain gorillas (Gorilla beringei beringei) are described as being quite large with a strongly flared jaw. They are shaggier and have angular nostrils (Groves, 2001). Gorillas live in polygynous cohesive groups that contain several females, their offspring and one or two males (Robbins et al., 2001). Gorillas also exhibit pronounce sexual dimorphism with males being nearly twice the size of the females. Mountain gorillas exhibit the largest degree of sexual dimorphism (Stewart and Harcourt, 1987) Sexual dimorphism suggests severe competition between males for females (Robbins et al., 2001). However, some males will be unable to attract females. They will likely have lower reproduction outputs when compared to dominant males (Harcourt, 1987; Robbins et al., 2001).

Gorillas live in polygynous cohesive groups that contain several females, their offspring and one or two males (Robbins et al., 2001). Gorillas also exhibit pronounce sexual dimorphism with males being nearly twice the size of the females. Mountain gorillas exhibit the largest degree of sexual dimorphism (Stewart and Harcourt, 1987) Sexual dimorphism suggests severe competition between males for females (Robbins et al., 2001). However, some males will be unable to attract females. They will likely have lower reproduction outputs when compared to dominant males (Harcourt, 1987; Robbins et al., 2001). Females generally exhibit natal dispersal as a mechanism to avoid inbreeding (Stewart and Harcourt, 1987). Young adult males will often be at the peripheries and will emigrate out of their natal group. Following their emigration, they will likely be solitary or join a group of bachelor males prior to attempting to take over a group of females (Stewart and Harcourt, 1987). Females generally give birth to their first infant at 10 years of age. Generally, they exhibit a birth ratio of 3.92. When they have infants, females tend to spend more time with the dominant male (Robbins et al., 2001).

Females generally exhibit natal dispersal as a mechanism to avoid inbreeding (Stewart and Harcourt, 1987). Young adult males will often be at the peripheries and will emigrate out of their natal group. Following their emigration, they will likely be solitary or join a group of bachelor males prior to attempting to take over a group of females (Stewart and Harcourt, 1987). Females generally give birth to their first infant at 10 years of age. Generally, they exhibit a birth ratio of 3.92. When they have infants, females tend to spend more time with the dominant male (Robbins et al., 2001). Gorillas (eastern and western lowland gorillas) are sympatric with chimpanzees due to their reliance on fruit (Robbins et al., 2001). Mountain gorilla’s territories do not overlap with chimpanzees. The main predators of gorillas are leopards (Panthera pardus) (Fay et al., 1995). Fay et al, (1995) documented an adult male gorilla remains being found on a leopard’s face.

Gorillas (eastern and western lowland gorillas) are sympatric with chimpanzees due to their reliance on fruit (Robbins et al., 2001). Mountain gorilla’s territories do not overlap with chimpanzees. The main predators of gorillas are leopards (Panthera pardus) (Fay et al., 1995). Fay et al, (1995) documented an adult male gorilla remains being found on a leopard’s face.

Female dominace is exhibited by most lemur species and involves the ability for the female to consistently evoke submissive behavior from all males (Jolly, 1966; Richard, 1987; Kappeler, 1993). emale dominance can only occur in contexts of male submission (Hrdy, 1981). When males exhibit spontaneous male submission to females in the absence of female aggression, this is termed deference (Kappeler, 1993a). In the absence of male deferential behavior, females can elicit submissive male behavior through the use of aggression (Sauther, 1993).

Female dominace is exhibited by most lemur species and involves the ability for the female to consistently evoke submissive behavior from all males (Jolly, 1966; Richard, 1987; Kappeler, 1993). emale dominance can only occur in contexts of male submission (Hrdy, 1981). When males exhibit spontaneous male submission to females in the absence of female aggression, this is termed deference (Kappeler, 1993a). In the absence of male deferential behavior, females can elicit submissive male behavior through the use of aggression (Sauther, 1993). Another animal that has shown female dominance is the spotted hyena (Kruuk, 1972; Frank, 1989; Smale et al., 1993). However, they do not exhibit true female dominance, as seen in lemurs, since female hyenas do not consistently dominate males in all contexts (Smale et al., 1993; Frank et al., 1989). Jolly (1966) found most dominance interactions that occur among lemurs occur in the context of feeding and often occur with the female supplanting the males. Female lemurs will have feeding priority after winning aggressive interactions with males who submissively vocalize and retreat (Jolly, 1966, 1967, 1984).Ring-tail lemurs lack sexual dimorphism, both females and males are the same size (Mittermeier et al., 1994; Sussman, 2000).

Another animal that has shown female dominance is the spotted hyena (Kruuk, 1972; Frank, 1989; Smale et al., 1993). However, they do not exhibit true female dominance, as seen in lemurs, since female hyenas do not consistently dominate males in all contexts (Smale et al., 1993; Frank et al., 1989). Jolly (1966) found most dominance interactions that occur among lemurs occur in the context of feeding and often occur with the female supplanting the males. Female lemurs will have feeding priority after winning aggressive interactions with males who submissively vocalize and retreat (Jolly, 1966, 1967, 1984).Ring-tail lemurs lack sexual dimorphism, both females and males are the same size (Mittermeier et al., 1994; Sussman, 2000).

catta are endemic to southwestern Madagascar (Sussman, 1977). Madagascar is located 800 kilometers from Southeast Africa. It is the fourth largest island in the world (Swindler, 2002). Southern Madagascar is characterized by a rainy season that occurs from November to March (Jolly, 1966). L. catta are mainly found in forests of dry bush, gallery, deciduous, scrub and closed canopy forests (Mittermeier et al., 1994). L. catta are opportunistic omnivores and their diet mainly consists of fruit, leaves, flowers, herbs, other plant parts, and sap (Sauther, 1992; Mittermeier et al., 1994). Sauther (1992) found that 30% to 60% of their diet consisted of feeding on fruit and 30% to 51% of their diet consisted on feeding on leaves and herbs.

catta are endemic to southwestern Madagascar (Sussman, 1977). Madagascar is located 800 kilometers from Southeast Africa. It is the fourth largest island in the world (Swindler, 2002). Southern Madagascar is characterized by a rainy season that occurs from November to March (Jolly, 1966). L. catta are mainly found in forests of dry bush, gallery, deciduous, scrub and closed canopy forests (Mittermeier et al., 1994). L. catta are opportunistic omnivores and their diet mainly consists of fruit, leaves, flowers, herbs, other plant parts, and sap (Sauther, 1992; Mittermeier et al., 1994). Sauther (1992) found that 30% to 60% of their diet consisted of feeding on fruit and 30% to 51% of their diet consisted on feeding on leaves and herbs. catta live in multi male, multi female groups ranging from nine to twenty two animals but on average have groups of fourteen animals (Sauther, 1991; Sussman, 1991). Females are philopatric and males disperse; dispersing males tend to enter new groups with one or two other males from their original groups (Sauther, 1991; Sussman, 1991). Generally one female is the single highest-ranking female. The highest-ranking female is typically the one to initiate group movement in a certain direction (Jolly, 1966; Sauther and Sussman, 1993). Females form a dominance hierarchy in which certain females will out rank other females depending on the matriline to which they belong; however, every female is more dominant than males. These dominance relations are reinforced by agonistic encounters (Jolly, 1966; Taylor and Sussman, 1985; Gould et al., 1999).

catta live in multi male, multi female groups ranging from nine to twenty two animals but on average have groups of fourteen animals (Sauther, 1991; Sussman, 1991). Females are philopatric and males disperse; dispersing males tend to enter new groups with one or two other males from their original groups (Sauther, 1991; Sussman, 1991). Generally one female is the single highest-ranking female. The highest-ranking female is typically the one to initiate group movement in a certain direction (Jolly, 1966; Sauther and Sussman, 1993). Females form a dominance hierarchy in which certain females will out rank other females depending on the matriline to which they belong; however, every female is more dominant than males. These dominance relations are reinforced by agonistic encounters (Jolly, 1966; Taylor and Sussman, 1985; Gould et al., 1999). Males within these social groups are peripheral; however, there are often one to three central/dominant males. The male hierarchy is often dependent on age (Sussman, 1992). Generally the central males are more fit than other males, while the lower ranking/peripheral males are older, recently transferred males as well as younger males that have yet to transfer (Sussman, 1991; 1992; Gould, 1996; Gould et al., 1999). The higher-ranking males often have more interactions with females and thus are more likely to mate, but lower-ranking males also mate (Sussman, 1991, 1992; Gould, 1994, 1996; Gould et al., 1999).

Males within these social groups are peripheral; however, there are often one to three central/dominant males. The male hierarchy is often dependent on age (Sussman, 1992). Generally the central males are more fit than other males, while the lower ranking/peripheral males are older, recently transferred males as well as younger males that have yet to transfer (Sussman, 1991; 1992; Gould, 1996; Gould et al., 1999). The higher-ranking males often have more interactions with females and thus are more likely to mate, but lower-ranking males also mate (Sussman, 1991, 1992; Gould, 1994, 1996; Gould et al., 1999). Females start reproducing when they are two or three years old and generally havean interbirth ratio of 2 to 3 years (Sauther, 1991). Mating activity in a group will normally last for two to three weeks per year (Sauther, 1991), however, each individual female will only be sexually receptive for one to two days per year (Van Horn and Resko, 1977; Sauther, 1991).

Females start reproducing when they are two or three years old and generally havean interbirth ratio of 2 to 3 years (Sauther, 1991). Mating activity in a group will normally last for two to three weeks per year (Sauther, 1991), however, each individual female will only be sexually receptive for one to two days per year (Van Horn and Resko, 1977; Sauther, 1991).