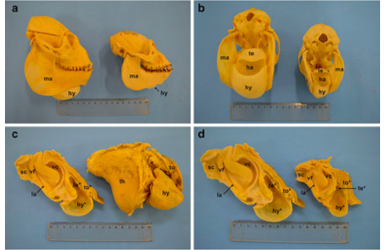

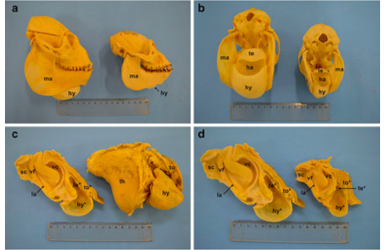

Howler monkeys are characterized by their enlarged hyoid bone and their ability to produce distinct loud calls (Baldwin and Baldwin, 1976; Kelemen and Sade, 1960; Schon, 1986; 1988; Mittermeier et al., 1998; Dunn et al., 2015).The structure of the hyoid bone is cup like with large hollow air sacs located on either side of the bone (Schönn, 1971). The large hollow air sacs help produce the resonating loud calls (Schönn, 1971; Mittermeier et al., 1998; Dunn et al., 2015). All species of howler monkeys are characterized by the enlargement of their hyoid bone (Mittermeier et al., 1998). However, they exhibit considerable variation in size and morphology (Hershkovitz, 1949; Dunn et al., 2015). Howler monkeys located in Central America tend to have smaller hyoid bones compared to their South American relatives (Hershkovitz, 1949; Dunn et al., 2015; Kowalewski et al., 2015).

Howler monkeys are characterized by their enlarged hyoid bone and their ability to produce distinct loud calls (Baldwin and Baldwin, 1976; Kelemen and Sade, 1960; Schon, 1986; 1988; Mittermeier et al., 1998; Dunn et al., 2015).The structure of the hyoid bone is cup like with large hollow air sacs located on either side of the bone (Schönn, 1971). The large hollow air sacs help produce the resonating loud calls (Schönn, 1971; Mittermeier et al., 1998; Dunn et al., 2015). All species of howler monkeys are characterized by the enlargement of their hyoid bone (Mittermeier et al., 1998). However, they exhibit considerable variation in size and morphology (Hershkovitz, 1949; Dunn et al., 2015). Howler monkeys located in Central America tend to have smaller hyoid bones compared to their South American relatives (Hershkovitz, 1949; Dunn et al., 2015; Kowalewski et al., 2015).

The hyoid bone in most mammals is an attachment point for muscles and ligaments. These muscles and ligaments are important for the functions of the mandible, tongue, laryngeal cartilages, pharynx, sternum, and cranial base. The hyoid bon is essential to many activities including swallowing, respiration and vocalizations (Howes, 1908; Negus 1949; Youlatos et al., 2015). The hyoid bone in howler monkeys unlike the human hyoid bone (does not articulate with any other bone) attaches through cartilaginous or ossified material to the cranial base (Howes, 1896).

The hyoid bone in most mammals is an attachment point for muscles and ligaments. These muscles and ligaments are important for the functions of the mandible, tongue, laryngeal cartilages, pharynx, sternum, and cranial base. The hyoid bon is essential to many activities including swallowing, respiration and vocalizations (Howes, 1908; Negus 1949; Youlatos et al., 2015). The hyoid bone in howler monkeys unlike the human hyoid bone (does not articulate with any other bone) attaches through cartilaginous or ossified material to the cranial base (Howes, 1896).

Morphologically the howler monkey hyoid bone is large, inflated and hollow (Hershkovtiz, 1949; Gregorin, 2006). The hyoid bone, bullae and the air sacs are collectively referred to as the hyoid apparatus (da Cunha et al., 2015). When the glottis produces low frequency sounds the hyoid and air sacs function as resonators (Schön-Ybarra, 1988). The hyoid bone is essential in the production of loud and low frequencies (Riede et al., 2008; de Boer, 2009). The harshness of the roars are a result of the force passage of air resulting in irregular noisy vibrations (Schön-Ybarra, 1986).

Morphologically the howler monkey hyoid bone is large, inflated and hollow (Hershkovtiz, 1949; Gregorin, 2006). The hyoid bone, bullae and the air sacs are collectively referred to as the hyoid apparatus (da Cunha et al., 2015). When the glottis produces low frequency sounds the hyoid and air sacs function as resonators (Schön-Ybarra, 1988). The hyoid bone is essential in the production of loud and low frequencies (Riede et al., 2008; de Boer, 2009). The harshness of the roars are a result of the force passage of air resulting in irregular noisy vibrations (Schön-Ybarra, 1986).

The exact mechanisms and the affect of the variation of loud calling has been heavily debated. Whitehead (1995) argued the loud calls were produced by both the hyoid bone, the sub-glottal and supra-glottal. Kelemen and Sade (1960) suggested the rigid cavities in the hyoid bullae and the nonrigid lateral sacs to be responsible for the loudness of the howler monkey calls. Kelemen and Sade (1960) further proposed the capacity to regulate their vocalizations is diminished due to the rigidity of the laryngeal organ and thyroid cartilage. Schön-Ybarra (1964) however showed howler monkeys had vocal plasticity due to their ability to lengthen and widen their mouth chambers rather than the morphology of their hyoid bone. Riede et al., (2008) also illustrated the interactions of the vocal cords and vocal tract allowing for changes in pitch. Schön-Ybarra (1986) suggested the vocalizations were produced due to the constriction of the laryngeal inlet which resulted in increasing sub-glottal pressure that is released over the vocal folds that in turn add pressure to the thyrohyoid canal and on the hyoid bullae which then resonates the glottally derived sounds resulting in the resonating loud calls (Schön 1986; 1971).

Howler monkeys will most often vocalize when responding to vocalizations of nearby groups and extra groups individuals (Whitehead, 1987). Howler monkeys may also vocalize when individuals become separated or when startled. This specialization of the hyoid apparatus suggests a prominent role in howler monkey social behaviors (da Cunha and Byrne, 2006). However, there is a lack in agreement of the function of loud calls (de Cunha and Jallles-Filho, 2007) this may stem from the variation of calls produce by howler monkeys (Belle et al., 2014).

Howler monkeys will most often vocalize when responding to vocalizations of nearby groups and extra groups individuals (Whitehead, 1987). Howler monkeys may also vocalize when individuals become separated or when startled. This specialization of the hyoid apparatus suggests a prominent role in howler monkey social behaviors (da Cunha and Byrne, 2006). However, there is a lack in agreement of the function of loud calls (de Cunha and Jallles-Filho, 2007) this may stem from the variation of calls produce by howler monkeys (Belle et al., 2014).

Howling or loud calling may occur in defense of an ecological resource such as a fruiting tree (Sekulic, 1982; Whitehead 1987; Chiarello, 1995; Holzmann et al., 2002). Another function of the loud calling may be mate defense in which the resident male of the group will loud call in response to extra group males, who may later attempt extra group copulation (Kowalewski and Garber, 2010; Fialho and Setz, 2007). The loud call may also function as defense against infanticidal males. Males may loud call toward extra group males in an attempt to prevent take overs from extra group males (Kitchen, 2004). Loud calling also appears to allow for spacing of the groups (Darwin, 1871; Carpenter, 1934; Sekulic, 1982). The hyoid bone provides howler monkeys with distinct roars that are essential for the determination of fitness (Dunn et al., 2015), food resource defense mate.

Howling or loud calling may occur in defense of an ecological resource such as a fruiting tree (Sekulic, 1982; Whitehead 1987; Chiarello, 1995; Holzmann et al., 2002). Another function of the loud calling may be mate defense in which the resident male of the group will loud call in response to extra group males, who may later attempt extra group copulation (Kowalewski and Garber, 2010; Fialho and Setz, 2007). The loud call may also function as defense against infanticidal males. Males may loud call toward extra group males in an attempt to prevent take overs from extra group males (Kitchen, 2004). Loud calling also appears to allow for spacing of the groups (Darwin, 1871; Carpenter, 1934; Sekulic, 1982). The hyoid bone provides howler monkeys with distinct roars that are essential for the determination of fitness (Dunn et al., 2015), food resource defense mate.

Read more/citations

Baldwin JD, Baldwin JI. (1976) Vocalizations of howler monkeys (Alouatta palliata) in southwestern Panama. Folia Primatologica 26:81–108.

Van Belle, S., Estrada, A., and Garber, P.A. (2014) The function of loud calls in black howler monkeys (Alouatta pigra): food, mate, or infant defense? American Journal of Primatology 76, 1196–1206.

Bergman, T. J., Cortés-Ortiz, L., Dias, P. A.D., Ho, L., Adams, D., Canales-Espinosa, D. and Kitchen, D. M. (2016) Striking differences in the loud calls of howler monkey sister species (Alouatta pigra and A. palliata). American Journal of Primatology., 78: 755–766.

Carpenter CR. (1934) A field study of the behavior and social relations of howling monkeys (Alouatta palliata). Comparative Psychology Monographs 10:1–168.

Chiarello AG. (1995) Role of loud calls in brown howler monkeys, Alouatta fusca. American Journal of Primatology 36:213–222.

Chivers DJ. (1969) On the daily behaviour and spacing of howling monkey groups. Folia Primatologica 10:48–102.

Cortes-Ortiz L, Bermingham E, Rico C, Rodrıguez-Luna E, Sampaio I, Ruiz-Garcia, M. (2003) Molecular systematics and biogeography of the Neotropical monkey genus, Alouatta. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 26:64–81.

de Boer, B. (2008) The acoustic role of supralaryngeal air sacs. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 123(5 Pt 2), 3732–3733.

de Boer, B. (2009) Acoustic analysis of primate air sacs and their effect on vocalization. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 126:3329–3343.

De Boer, B., & Aclc. (2010) Investigating the acoustic effect of the descended larynx with articulatory models. Journal of Phonetics, 38(4), 679-686.

da Cunha RGT, Byrne RW. (2006) Roars of black howler monkeys (Alouatta caraya): evidence for a function in inter‐ group spacing. Behaviour 143:1169–1199.

da Cunha RGT, Jalles‐Filho E. (2007) The roaring of Southern brown howler monkeys (Alouatta guariba clamitans) as a mechanism of active defence of borders. Folia Primatologica 78:259–271.

da Cunha RGT, de Oliveira DAG, Holzmann I, Kitchen DM. (2015) Production of loud and quiet calls in howler monkeys. In: Kowalewski MM, Garber PA, Cortes-Ortiz L, Urbani B, Youlatos D, editors. Howler monkeys: adaptive radiation, systematics, and morphology. New York: Springer Press. p 337–368.

Darwin C. (1871) The descent of man and selection in relation to sex. London: John Murray.

Di Fiore A, Campbell CJ. (2007) The Atelines: variation in ecology, behavior, and social organization. In: Campbell CJ, Fuentes A, MacKinnon KC, Panger M, Bearder SK, editors. Primates in perspective. New York: Oxford U Pr. p 155-85.

Dunn JC, Halenar LB, Davies TG, et al. (2015) Evolutionary trade-off between vocal tract and testes dimensions in howler monkeys. Current Biology 25:2839–2844.

Fialho MS, Setz EZF. (2007) Extragroup copulations among brown howler monkeys in southern Brazil. Neotropic Primates 14:28–30.

Gregorin R (2006) Taxonomy and geographic variation of species of the genus Alouatta Lacépède (Primates, Atelidae) in Brazil. Rev Bras Zoology 23:64–144.

Hershkovitz, P. (1949) Mammals of northern Colombia. Preliminary report No. 4: Monkeys (Primates) with taxonomic revisions of some forms. Proceedings of the United States National Museum 98: 323–427.

Hill, W. C. O. (1962) Primates Comparative Anatomy and Taxonomy V. Cebidae Part B. Edinburgh University Press, Edinburgh, Scotland.

Hillowala, R. A., and Lass, N. J. (1978) “Spectrographic analysis of air sac resonance in rhesus monkeys,” American Journal of Physical Anthropology 49, 129–132.

Holzmann I, Agostini I, Di Bitetti M. (2012) Roaring behavior of two syntopic howler species (Alouatta caraya and A. guariba clamitans): evidence supports the mate defense hypothesis. International Journal of Primatology 33:338–355.

Howes GB. (1896) The mammalian hyoid, with especial Reference to that of Lepus, Hyrax, and Choloepus. Journal Anatomy Physiology. 30:513–526.

Kelemen G, Sade J (1960) The vocal organ of the howling monkey, Alouatta palliata. Journal of Morphology 107:123–140.

Kitchen DM. (2006) Experimental test of female black howler monkey (Alouatta pigra) responses to loud calls from potentially infanticidal males: effects of numeric odds, vulnerable offspring, and companion behavior. American Journal of Physical Anthropology 131:73–83.

Kitchen DM. (2004) Alpha male black howler monkey responses to loud calls: effect of numeric odds, male companion behaviour and reproductive investment. Animal Behaviour 67:125–139.

Kitchen DM, Horwich RH, James RA. (2004) Subordinate male black howler monkey (Alouatta pigra) responses to loud calls: experimental evidence for the effects of intra‐group male relationships and age. Behaviour 141:703–723.

Kowalewski MM, Garber PA. (2010) Mating promiscuity and reproductive tactics in female black and gold howler monkeys (Alouatta caraya) inhabiting an island on the Parana river, Argentina. American Journal of Primatology 71:1–15.

Kowalewski, M. M., Garber, P. A., Cort s-Ortiz, L., Urbani, B., & Youlatos, D. (2015) Howler Monkeys Behavior, Ecology, and Conservation. New York, NY: Springer.

Mittermeier, R.A., Myers, N., Thomsen, J.R., da Fonseca, G. A.B. and Olivieri, S. (1998) Biodiversity hotspots and major tropical wilderness areas: approaches to setting conservation priorities. Conservation Biology 12, 516-20.

Negus, V. E. (1949) The Comparative Anatomy and Physiology of the Larynx William Heinemann Medical Books Ltd., London .

Riede T, Tokuda IT, Munger JB, Thomson SL. (2008) Mammalian laryngseal air sacs add variability to the vocal tract impedance: physical and computational modeling. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 124:634–647.

Schön MA (1964) Possible function of some pharyngeal and lingual muscles of the howling mon- key (Alouatta seniculus). Acta Anatomy 58:271–283.

Schön MA. (1971) The anatomy of the resonating mechanism in howling monkeys. Folia Primatologica 15:117–132.

Schön Ybarra MA. (1986) Loud calls of adult male red howling monkeys (Alouatta seniculus). Folia Primatologica 47:204–216.

Schön Ybarra MA (1988) Morphological adaptations for loud phonations in the vocal organ of howling monkeys. Primate Rep 22:19–24.

Schön-Ybarra MA. (1995) A comparative approach to the nonhuman primate vocal tract: implications for sound production. In: Zimmerman E, Newman JD, editors. Frontiers in primate vocal communication. New York: Plenum Press. p 185–198.

Sekulic R, Chivers DJ. (1986) The significance of call duration in howler monkeys. International Journal of Primatology 7:183–190.

Thorington RW, Ruiz JC, Eisenberg JF (1984) A study of black howler monkeys (Alouatta caraya) populations in northern Argentina. American Journal of Primatology 6:357–366.

Whitehead JM. (1987) Vocally mediated reciprocity between neighbouring groups of mantled howling monkeys, Alouatta palliata palliata. Animal Behavior 35:1615–1627.

Whitehead JM. (1989) The effect of the location of a simulated intruder on responses to long-distance vocalizations of mantled howling monkeys, Alouatta palliata palliata. Behavior 108:73–103.

Whitehead JM. (1995) Vox Alouattinae: a preliminary survey of the acoustic characteristics of long-distance calls of howling monkeys. International Journal of Primatology 16:121–144.

Youlatos D, Couette S, Halenar LB. (2015) Morphology of howler monkeys: a review and quantitative analyses. In: Kowalewski MM, Garber PA, Cort es-Ortiz L, Urbani B, Youlatos D, editors. Howler monkeys: adaptive radiation, systematics, and morphology. New York: Springer Press.

The taxonomic group of Strepsirrhines are characterized by a rhinarium leading to a greater reliance on olfaction. Strepsirrhines includes lemurs, lorises, pottos and galagos. Haplorrhines also exhibit increased parental care, increase gestation length and slower life history (Chimps live until their 50s while Lemurs live until their twenties) (Streir, 2011). Haplorhines due to their decreased reliance on smell tends to be more dependent on vision and thus have forward facing eyes with increased color vision. Anatomically their have a bony plate at the back of their head and a fused mandible (Gebo, 2014).

The taxonomic group of Strepsirrhines are characterized by a rhinarium leading to a greater reliance on olfaction. Strepsirrhines includes lemurs, lorises, pottos and galagos. Haplorrhines also exhibit increased parental care, increase gestation length and slower life history (Chimps live until their 50s while Lemurs live until their twenties) (Streir, 2011). Haplorhines due to their decreased reliance on smell tends to be more dependent on vision and thus have forward facing eyes with increased color vision. Anatomically their have a bony plate at the back of their head and a fused mandible (Gebo, 2014). Haplorhines can be split into two groups platyrrhines and catarrhines. Platyrrhines include new world monkeys while Catarrhines include old world monkeys and apes. Apes include great apes and lesser apes differentiated based upon their body size. Lesser apes tend to weigh less then 12 kg while great apes weight between 30 to 100 kg. Lesser apes include gibbons while greater apes include gorillas, orangutans and humans (Strier, 2011).

Haplorhines can be split into two groups platyrrhines and catarrhines. Platyrrhines include new world monkeys while Catarrhines include old world monkeys and apes. Apes include great apes and lesser apes differentiated based upon their body size. Lesser apes tend to weigh less then 12 kg while great apes weight between 30 to 100 kg. Lesser apes include gibbons while greater apes include gorillas, orangutans and humans (Strier, 2011). Apes exhibit several characteristics that separate them from monkeys and strepsirrhines. Cranially they are characterized by broader palates, broader nasal region and larger brains (Fleagle, 2013). This larger brain allows for more complex brain and cognitive abilities. Behaviorally they exhibit a longer period of gestation and parental care (Gebo, 2014). Their axial skeleton lacks a tail (Strier, 2011) leading to a reduced lumbar region, and an expanded sacrum (Fleagle, 2013). They have and broad thorax and dorsally position scapula. This allows for greater shoulder movement (circumduction) (Fleagle, 2013; Gebo, 2014). They tend to have a shorter lower back with increased stability. Their arms tend to be longer then their legs (except humans) for brachiation (Fleagle, 2013; Gebo, 2014). Apes also exhibit a spool shaped trochlea on the humerus and short olecranon process at the ulna (elbow region). Their wrist does not articulate at the carpal bones. They have a fibrous meniscus that separates the two bones. They have a broad ilium (blade like part of the pelvis). They have broad femoral condyles and a robust hallux (foot bone) (Fleagle, 2013).

Apes exhibit several characteristics that separate them from monkeys and strepsirrhines. Cranially they are characterized by broader palates, broader nasal region and larger brains (Fleagle, 2013). This larger brain allows for more complex brain and cognitive abilities. Behaviorally they exhibit a longer period of gestation and parental care (Gebo, 2014). Their axial skeleton lacks a tail (Strier, 2011) leading to a reduced lumbar region, and an expanded sacrum (Fleagle, 2013). They have and broad thorax and dorsally position scapula. This allows for greater shoulder movement (circumduction) (Fleagle, 2013; Gebo, 2014). They tend to have a shorter lower back with increased stability. Their arms tend to be longer then their legs (except humans) for brachiation (Fleagle, 2013; Gebo, 2014). Apes also exhibit a spool shaped trochlea on the humerus and short olecranon process at the ulna (elbow region). Their wrist does not articulate at the carpal bones. They have a fibrous meniscus that separates the two bones. They have a broad ilium (blade like part of the pelvis). They have broad femoral condyles and a robust hallux (foot bone) (Fleagle, 2013).

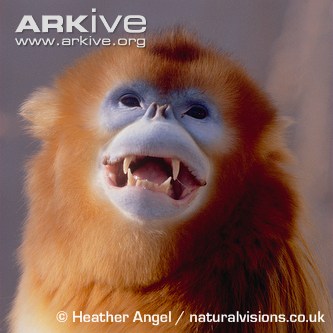

The genus snub-nosed monkeys (Rhinopithecus) consists of 5 species (3 are endemic to China). The golden snub-nosed monkey or Sichuan snub nosed monkey is brightly colored species found in the Sichuan mountains (Liu et al., 2012) Golden snub-nosed monkeys are Old World Monkeys (Catarrhini). Old world monkeys are made up of Colobinae and Cercopithinae. Golden snub-nosed monkeys are part of Colobinae subfamily (Grover, 2001). A group characterized by leaf eating (Liu et al., 2012). The first described snub-nosed monkeys were named by Milne-Edwards in 1870s. Roxellana was a concubine of the Suleiman the Magnificent (Napier, 1970).

The genus snub-nosed monkeys (Rhinopithecus) consists of 5 species (3 are endemic to China). The golden snub-nosed monkey or Sichuan snub nosed monkey is brightly colored species found in the Sichuan mountains (Liu et al., 2012) Golden snub-nosed monkeys are Old World Monkeys (Catarrhini). Old world monkeys are made up of Colobinae and Cercopithinae. Golden snub-nosed monkeys are part of Colobinae subfamily (Grover, 2001). A group characterized by leaf eating (Liu et al., 2012). The first described snub-nosed monkeys were named by Milne-Edwards in 1870s. Roxellana was a concubine of the Suleiman the Magnificent (Napier, 1970). Golden snub-nosed monkeys are brightly colored with a prominent upturned nose. They have flap over their nostrils, a tail shorter than their body (characteristic of old world monkeys). Their body color is yellow with varying tones from brown to bright orange-red. They also have a thick black stripe down their back (Groves, 2001).

Golden snub-nosed monkeys are brightly colored with a prominent upturned nose. They have flap over their nostrils, a tail shorter than their body (characteristic of old world monkeys). Their body color is yellow with varying tones from brown to bright orange-red. They also have a thick black stripe down their back (Groves, 2001). They are located in central and western china (Grover, 2001). They are found in four proveniences of china including the eastern edge of the Qinghai Tibet Plateau and Central China, the Qinling mountains (Shaanixi province), the Minshan mountain (Gansu Province), the Qinghai mountains and Minshan mountains (Sichuan Province) and the Daba mountain (Hubei Province). They are found largely in the Shennongiia forest. Like they panda they are considered a national animal icon (Liu et al., 2012).

They are located in central and western china (Grover, 2001). They are found in four proveniences of china including the eastern edge of the Qinghai Tibet Plateau and Central China, the Qinling mountains (Shaanixi province), the Minshan mountain (Gansu Province), the Qinghai mountains and Minshan mountains (Sichuan Province) and the Daba mountain (Hubei Province). They are found largely in the Shennongiia forest. Like they panda they are considered a national animal icon (Liu et al., 2012). Golden snub-nosed monkeys like other Colobines are primarily arboreal herbivores (Liu et al., 2012). They live at altitudes of 1400-3400 meters. They live in the three types of habitats; mixed evergreen, deciduous broadleaf forests and mixed deciduous and conifer forest. These forests are characterized by winters that lead to food scarcity. They are primarily folivorious but will also eat buds, fruits, barks, lichens and insects and their diet changes seasonally (Li and Jiang, 2010). They mainly eat lichen (43% of the diet) (Liu et al., 2013).

Golden snub-nosed monkeys like other Colobines are primarily arboreal herbivores (Liu et al., 2012). They live at altitudes of 1400-3400 meters. They live in the three types of habitats; mixed evergreen, deciduous broadleaf forests and mixed deciduous and conifer forest. These forests are characterized by winters that lead to food scarcity. They are primarily folivorious but will also eat buds, fruits, barks, lichens and insects and their diet changes seasonally (Li and Jiang, 2010). They mainly eat lichen (43% of the diet) (Liu et al., 2013). Golden snub-nosed monkeys are found in large groups of 50-600 groups (Luo et al., 2014). One subgroup of the larger groups is a one male unit (OMU) which consist of one male and several females with their offspring (Li and Jiang, 2010; Li and Zhoa, 2007). This group system is similar to Gorillas. The second sub group consists of all males (adults and subadults). They are often close in proximity to the OMUs but are not allow mating rights since the males of the one male units monopolize the females (Yoa, 2016; Li and Jiang, 2010). However, females will often move between the OMU and mate with extra unit males (Luo et al., 2014). Extra group males appear to father half of the offspring within the large groups (Yoa, 2016).

Golden snub-nosed monkeys are found in large groups of 50-600 groups (Luo et al., 2014). One subgroup of the larger groups is a one male unit (OMU) which consist of one male and several females with their offspring (Li and Jiang, 2010; Li and Zhoa, 2007). This group system is similar to Gorillas. The second sub group consists of all males (adults and subadults). They are often close in proximity to the OMUs but are not allow mating rights since the males of the one male units monopolize the females (Yoa, 2016; Li and Jiang, 2010). However, females will often move between the OMU and mate with extra unit males (Luo et al., 2014). Extra group males appear to father half of the offspring within the large groups (Yoa, 2016). Golden snub-nosed monkeys breed seasonally. Most births occur during March to May peaking in April. Copulations occur in September and November. They look give birth during this time because of its overlap with spring and the growth of the preferred food season (Li and Zhoa, 2007). Millar (1977) argued this developed in order to fulfill the energetic needs of lactation. Females are pregnant for 6 months (ranging from 193-204 days). Females generally initiates all copulations similar to other Colobines (Western black and white Colobines) (Li an Zhoa, 2007).

Golden snub-nosed monkeys breed seasonally. Most births occur during March to May peaking in April. Copulations occur in September and November. They look give birth during this time because of its overlap with spring and the growth of the preferred food season (Li and Zhoa, 2007). Millar (1977) argued this developed in order to fulfill the energetic needs of lactation. Females are pregnant for 6 months (ranging from 193-204 days). Females generally initiates all copulations similar to other Colobines (Western black and white Colobines) (Li an Zhoa, 2007).

Howler monkeys

Howler monkeys The hyoid bone in most mammals is an attachment point for muscles and ligaments. These muscles and ligaments are important for the functions of the mandible, tongue, laryngeal cartilages, pharynx, sternum, and cranial base. The hyoid bon is essential to many activities including swallowing, respiration and vocalizations (Howes, 1908; Negus 1949; Youlatos et al., 2015). The hyoid bone in howler monkeys unlike the human hyoid bone (does not articulate with any other bone) attaches through cartilaginous or ossified material to the cranial base (Howes, 1896).

The hyoid bone in most mammals is an attachment point for muscles and ligaments. These muscles and ligaments are important for the functions of the mandible, tongue, laryngeal cartilages, pharynx, sternum, and cranial base. The hyoid bon is essential to many activities including swallowing, respiration and vocalizations (Howes, 1908; Negus 1949; Youlatos et al., 2015). The hyoid bone in howler monkeys unlike the human hyoid bone (does not articulate with any other bone) attaches through cartilaginous or ossified material to the cranial base (Howes, 1896). Morphologically the howler monkey hyoid bone is large, inflated and hollow (Hershkovtiz, 1949; Gregorin, 2006). The hyoid bone, bullae and the air sacs are collectively referred to as the hyoid apparatus (da Cunha et al., 2015). When the glottis produces low frequency sounds the hyoid and air sacs function as resonators (Schön-Ybarra, 1988). The hyoid bone is essential in the production of loud and low frequencies (Riede et al., 2008; de Boer, 2009). The harshness of the roars are a result of the force passage of air resulting in irregular noisy vibrations (Schön-Ybarra, 1986).

Morphologically the howler monkey hyoid bone is large, inflated and hollow (Hershkovtiz, 1949; Gregorin, 2006). The hyoid bone, bullae and the air sacs are collectively referred to as the hyoid apparatus (da Cunha et al., 2015). When the glottis produces low frequency sounds the hyoid and air sacs function as resonators (Schön-Ybarra, 1988). The hyoid bone is essential in the production of loud and low frequencies (Riede et al., 2008; de Boer, 2009). The harshness of the roars are a result of the force passage of air resulting in irregular noisy vibrations (Schön-Ybarra, 1986).

Howler monkeys will most often vocalize when responding to vocalizations of nearby groups and extra groups individuals (Whitehead, 1987). Howler monkeys may also vocalize when individuals become separated or when startled. This specialization of the hyoid apparatus suggests a prominent role in howler monkey social behaviors (da Cunha and Byrne, 2006). However, there is a lack in agreement of the function of loud calls (de Cunha and Jallles-Filho, 2007) this may stem from the variation of calls produce by howler monkeys (Belle et al., 2014).

Howler monkeys will most often vocalize when responding to vocalizations of nearby groups and extra groups individuals (Whitehead, 1987). Howler monkeys may also vocalize when individuals become separated or when startled. This specialization of the hyoid apparatus suggests a prominent role in howler monkey social behaviors (da Cunha and Byrne, 2006). However, there is a lack in agreement of the function of loud calls (de Cunha and Jallles-Filho, 2007) this may stem from the variation of calls produce by howler monkeys (Belle et al., 2014). Howling or loud calling may occur in defense of an ecological resource such as a fruiting tree (Sekulic, 1982; Whitehead 1987; Chiarello, 1995; Holzmann et al., 2002). Another function of the loud calling may be mate defense in which the resident male of the group will loud call in response to extra group males, who may later attempt extra group copulation (Kowalewski and Garber, 2010; Fialho and Setz, 2007). The loud call may also function as defense against infanticidal males. Males may loud call toward extra group males in an attempt to prevent take overs from extra group males (Kitchen, 2004). Loud calling also appears to allow for spacing of the groups (Darwin, 1871; Carpenter, 1934; Sekulic, 1982). The hyoid bone provides howler monkeys with distinct roars that are essential for the determination of fitness (Dunn et al., 2015), food resource defense mate.

Howling or loud calling may occur in defense of an ecological resource such as a fruiting tree (Sekulic, 1982; Whitehead 1987; Chiarello, 1995; Holzmann et al., 2002). Another function of the loud calling may be mate defense in which the resident male of the group will loud call in response to extra group males, who may later attempt extra group copulation (Kowalewski and Garber, 2010; Fialho and Setz, 2007). The loud call may also function as defense against infanticidal males. Males may loud call toward extra group males in an attempt to prevent take overs from extra group males (Kitchen, 2004). Loud calling also appears to allow for spacing of the groups (Darwin, 1871; Carpenter, 1934; Sekulic, 1982). The hyoid bone provides howler monkeys with distinct roars that are essential for the determination of fitness (Dunn et al., 2015), food resource defense mate.

Howler monkeys (Genus: Aloutta) are part of the taxonomic group Platyrrhini (New World Monkeys). They are a subfamily of Atelinae. The Atelinae subfamily are characterized by their large size and their prehensile tail (Di Fiore, 2011; Groves 2001). Aloutta are widely spread in Central and South America.

Howler monkeys (Genus: Aloutta) are part of the taxonomic group Platyrrhini (New World Monkeys). They are a subfamily of Atelinae. The Atelinae subfamily are characterized by their large size and their prehensile tail (Di Fiore, 2011; Groves 2001). Aloutta are widely spread in Central and South America.

Howler monkeys live in several different ecosystems including tropical rainforests, dry deciduous forest, mountain forests, lowland forest and mangroves (Kowalewski et al., 2015). A. palliata live in forest ranging from close canopy ever green forest to deciduous woodlands. A. pigra are considered to be habitat specialists living in undisturbed tropical rainforest (Smith, 1970; Conservation biology of genus Alouatta). Many groups of howler monkeys live within forest fragments surrounding by cattle farms or agricultural area (Cortés-Ortiz et al., 2003).

Howler monkeys live in several different ecosystems including tropical rainforests, dry deciduous forest, mountain forests, lowland forest and mangroves (Kowalewski et al., 2015). A. palliata live in forest ranging from close canopy ever green forest to deciduous woodlands. A. pigra are considered to be habitat specialists living in undisturbed tropical rainforest (Smith, 1970; Conservation biology of genus Alouatta). Many groups of howler monkeys live within forest fragments surrounding by cattle farms or agricultural area (Cortés-Ortiz et al., 2003). Howler monkeys are characterized by their enlarged hyoid bone and their ability to produce distinct loud calls (Baldwin and Baldwin, 1976; Schon, 1986; 1988; Mittermeier et al., 1998). Howler monkeys are part of the Atelidae family and Atelinae subfamily (Di Fiore, 2011). They have one of the loudest primate vocalizations of the Neotropics (da Cuncha et al., 2015). The structure of the hyoid bone is cup like with large hollow air sacs located on either side of the bone (Schönn, 1971). The large hollow air sacs help produce the resonating loud calls (Schönn, 1971; Mittermeier et al., 1998). Like most other neotropic primates they are arboreal (Kowalewski et al., 2015).

Howler monkeys are characterized by their enlarged hyoid bone and their ability to produce distinct loud calls (Baldwin and Baldwin, 1976; Schon, 1986; 1988; Mittermeier et al., 1998). Howler monkeys are part of the Atelidae family and Atelinae subfamily (Di Fiore, 2011). They have one of the loudest primate vocalizations of the Neotropics (da Cuncha et al., 2015). The structure of the hyoid bone is cup like with large hollow air sacs located on either side of the bone (Schönn, 1971). The large hollow air sacs help produce the resonating loud calls (Schönn, 1971; Mittermeier et al., 1998). Like most other neotropic primates they are arboreal (Kowalewski et al., 2015). Howler monkeys live in groups of one to three adult males, several adult females and their offspring. Most species of Aloutta exhibit group sizes of 10-15 individuals with less than three males. This includes A. seniculus, A. carraya, A. guariba, and A. pigra. However, A. palliata (mantled howler monkeys) tend to have large groups with three or more adult males and nine or more females. The largest groups have been reported to be made up of up to forty individuals (Di Fiore, 2011; Chapman 1998).

Howler monkeys live in groups of one to three adult males, several adult females and their offspring. Most species of Aloutta exhibit group sizes of 10-15 individuals with less than three males. This includes A. seniculus, A. carraya, A. guariba, and A. pigra. However, A. palliata (mantled howler monkeys) tend to have large groups with three or more adult males and nine or more females. The largest groups have been reported to be made up of up to forty individuals (Di Fiore, 2011; Chapman 1998). Howler monkeys are generally folivorious but will supplement their diet with fruits (Di Fiore, 2011). Due to their folivorious diets they show adaptions for leave break down. This includes long retention times for digesting within the alimentary canal allowing for gut bacteria to break down the carbohydrates in leave (Di Fiore, 2011).

Howler monkeys are generally folivorious but will supplement their diet with fruits (Di Fiore, 2011). Due to their folivorious diets they show adaptions for leave break down. This includes long retention times for digesting within the alimentary canal allowing for gut bacteria to break down the carbohydrates in leave (Di Fiore, 2011). Overall Howler monkeys rely on slow digestion in order to efficiently extract energy from the leaf carbohydrates. They tend to eat immature leaves since this tend to have a higher ratio of protein and focus on plants with less plant secondary compounds (Di Fiore, 2011). They also tend to show energy minimization, meaning they rest for long periods of time to allow digestions of the leaves (Di Fiore, 2011).

Overall Howler monkeys rely on slow digestion in order to efficiently extract energy from the leaf carbohydrates. They tend to eat immature leaves since this tend to have a higher ratio of protein and focus on plants with less plant secondary compounds (Di Fiore, 2011). They also tend to show energy minimization, meaning they rest for long periods of time to allow digestions of the leaves (Di Fiore, 2011). Generally, both sexes will typically disperse from their natal groups before their first reproduction (Crockett, 1984; Di Fiore, 2011). However, female tends to disperse more often and move a further distance when compared to males (Di Fiore, 2011). Males disperse to attempt to take over a social group from an existing dominant male. Female howler monkeys of A. seniculus are targeted by older females within their natal groups leading to their dispersal. They often have difficulty integrating into existing social groups and will instead form new social groups with other dispersers. The new social group will establish a home range followed closely by breeding (Crockett, 1984; Di Fiore, 2011).

Generally, both sexes will typically disperse from their natal groups before their first reproduction (Crockett, 1984; Di Fiore, 2011). However, female tends to disperse more often and move a further distance when compared to males (Di Fiore, 2011). Males disperse to attempt to take over a social group from an existing dominant male. Female howler monkeys of A. seniculus are targeted by older females within their natal groups leading to their dispersal. They often have difficulty integrating into existing social groups and will instead form new social groups with other dispersers. The new social group will establish a home range followed closely by breeding (Crockett, 1984; Di Fiore, 2011). Howler monkeys exhibit sexual dimorphism with males being larger than females. A. caraya and A. guariba are sexually dichromatic (Kowalewski et al., 2015). Both males and females within the group form dominance hierarchy that are often correlated with age (within A. seniculus and A. palliata). Males are dominant over females and the dominant male tend to have more access to females. Dominant females often exhibit aggression toward subordinate females and their infants (Crockett, 1984; Di Fiore, 2011). Females within Aloutta paliatta exhibit their first reproduction as 4 years of age (Glanders, 1980; Crockett, 1984). Male take overs are often associated with high infant mortality relating to infanticide (40% disappeared infant) (Crockett, 1984). Females within A. seniculus exhibit a sex cycle of 26 days and 2-3 days of estrus. They gestate approximately for 191 days (Delfer, 2004). Several species exhibit tongue flicking prior to mating (Delfer, 2004)

Howler monkeys exhibit sexual dimorphism with males being larger than females. A. caraya and A. guariba are sexually dichromatic (Kowalewski et al., 2015). Both males and females within the group form dominance hierarchy that are often correlated with age (within A. seniculus and A. palliata). Males are dominant over females and the dominant male tend to have more access to females. Dominant females often exhibit aggression toward subordinate females and their infants (Crockett, 1984; Di Fiore, 2011). Females within Aloutta paliatta exhibit their first reproduction as 4 years of age (Glanders, 1980; Crockett, 1984). Male take overs are often associated with high infant mortality relating to infanticide (40% disappeared infant) (Crockett, 1984). Females within A. seniculus exhibit a sex cycle of 26 days and 2-3 days of estrus. They gestate approximately for 191 days (Delfer, 2004). Several species exhibit tongue flicking prior to mating (Delfer, 2004)

Primates exhibit a diversity of locomotion types from quadrupedalism to leaping (Napier and Walker, 1967; Hunt et al., 1996). A familiar locomotor category in primatology is vertical clinging and leaping (VCL). The main primate groups that exhibit this locomotion are tarsiers and some strepsirrhines. Tarsiers, indriids, sifakas, some galagos and calltrichids are morphological specialized for this specific locomotion (Napier and Walker; 1967; Terranova and Dagosto, 1994).Ashton and Oxnard (1964) were the first to attempt classifying primate locomotion based upon behavioral classifications.

Primates exhibit a diversity of locomotion types from quadrupedalism to leaping (Napier and Walker, 1967; Hunt et al., 1996). A familiar locomotor category in primatology is vertical clinging and leaping (VCL). The main primate groups that exhibit this locomotion are tarsiers and some strepsirrhines. Tarsiers, indriids, sifakas, some galagos and calltrichids are morphological specialized for this specific locomotion (Napier and Walker; 1967; Terranova and Dagosto, 1994).Ashton and Oxnard (1964) were the first to attempt classifying primate locomotion based upon behavioral classifications. Prost (1965) was important for his consideration of the difference between positional behaviors and locomotive behaviors. Napier and Walker (1967) argued for a new category type of prosimian (strepsirrhines and tarsiers) locomotion called vertical clinging and leaping. Vertical clinging and leaping involves the adopting of an orthograde (upright) posture at rest on a vertically oriented support that allows primates to initiate movement through extending their hind limbs. They then leap from one support to another whilst rotating their bodies to land on another vertical support (Napier and Walker, 1967; Stern and Oxnard, 1973; Demes et al., 1991; Crompton et al., 1993; Fleagle, 2013).

Prost (1965) was important for his consideration of the difference between positional behaviors and locomotive behaviors. Napier and Walker (1967) argued for a new category type of prosimian (strepsirrhines and tarsiers) locomotion called vertical clinging and leaping. Vertical clinging and leaping involves the adopting of an orthograde (upright) posture at rest on a vertically oriented support that allows primates to initiate movement through extending their hind limbs. They then leap from one support to another whilst rotating their bodies to land on another vertical support (Napier and Walker, 1967; Stern and Oxnard, 1973; Demes et al., 1991; Crompton et al., 1993; Fleagle, 2013). Most arboreal primates have been shown to exhibit vertical clinging (Dagosto, 1994; Fontain, 1990; Garber, 1991; Napier and Walker, 1967). Primates who most often apply vertical clinging and leaping are large bodied strepsirrhines, such as indris and sifakas, to small body primates, including galagos and tarsiers (Terranova and Dagosto, 1994) (Figure 1). Propithecus verreauxi (a large bodied lemur ranging from 3700 to 4280 grams) habitually uses vertical clinging and leaping (Napier and Walker, 1967; Smith and Jungers, 1977; Walker, 1979; Johnson, 2012). Propithecus coquereli is another example of large bodied habitual vertical clinging and leaping primate (Figure 2). Hapalemur (bamboo lemurs) also exhibits vertical clinging and leaping but infrequently when compared to other vertical clinging and leaping primates (Gebo, 2011).

Most arboreal primates have been shown to exhibit vertical clinging (Dagosto, 1994; Fontain, 1990; Garber, 1991; Napier and Walker, 1967). Primates who most often apply vertical clinging and leaping are large bodied strepsirrhines, such as indris and sifakas, to small body primates, including galagos and tarsiers (Terranova and Dagosto, 1994) (Figure 1). Propithecus verreauxi (a large bodied lemur ranging from 3700 to 4280 grams) habitually uses vertical clinging and leaping (Napier and Walker, 1967; Smith and Jungers, 1977; Walker, 1979; Johnson, 2012). Propithecus coquereli is another example of large bodied habitual vertical clinging and leaping primate (Figure 2). Hapalemur (bamboo lemurs) also exhibits vertical clinging and leaping but infrequently when compared to other vertical clinging and leaping primates (Gebo, 2011). Vertical clinging and leaping has also been observed in calltrichids (Napier and Walker, 1967; Crompton and Andau, 1986; Dagosto et al., 2001). Cartmill (1974) suggested that the nails of Callicebus sp. allow them to better move on vertical supports. Pygmy marmosets will often take position vertically on substrates to feed on sap allow them to make the vertical posture part of vertical clinging and leaping (Kinzey et al., 1975). A constraint on locomotion is often diet. For instance, indriids, sportive lemurs and bamboo lemurs have a low energy diet with their focus on leafy food resources. Folivory acts as a dietary constraint on vertical clinging and leaping, thus the morphological adaptions for vertical clinging and leaping differ depending on relative size and diet (Gebo, 2011).

Vertical clinging and leaping has also been observed in calltrichids (Napier and Walker, 1967; Crompton and Andau, 1986; Dagosto et al., 2001). Cartmill (1974) suggested that the nails of Callicebus sp. allow them to better move on vertical supports. Pygmy marmosets will often take position vertically on substrates to feed on sap allow them to make the vertical posture part of vertical clinging and leaping (Kinzey et al., 1975). A constraint on locomotion is often diet. For instance, indriids, sportive lemurs and bamboo lemurs have a low energy diet with their focus on leafy food resources. Folivory acts as a dietary constraint on vertical clinging and leaping, thus the morphological adaptions for vertical clinging and leaping differ depending on relative size and diet (Gebo, 2011). Napier and Walker (1967) argued vertical clinging and leaping to be the earliest locomotion specialization of primates. They suggested several features of vertical clinger and leapers could be related back to the posture/movement of Eocene primates thus the morphology of vertical clingers and leapers were pre-adaptive to the other primate locomotion adaptions (Napier and Walker, 1967). However, this hypothesis of vertical clinging and leaping as an early pre-adaptive trait was quickly challenged by Cartmill (1972), Martin (1972) and Stern and Oxnard (1973).

Napier and Walker (1967) argued vertical clinging and leaping to be the earliest locomotion specialization of primates. They suggested several features of vertical clinger and leapers could be related back to the posture/movement of Eocene primates thus the morphology of vertical clingers and leapers were pre-adaptive to the other primate locomotion adaptions (Napier and Walker, 1967). However, this hypothesis of vertical clinging and leaping as an early pre-adaptive trait was quickly challenged by Cartmill (1972), Martin (1972) and Stern and Oxnard (1973). Vertical clinging and leaping as an ancestral condition would not be possible since there is a lack of generalized morphology shared between haplorrhine and strepsirrhines vertical clingers and leapers. For example, the hind limb anatomies are different between differently sized species that practice vertical clinging and leaping and thus no overall anatomical pattern exists (Stern and Oxnard, 1973). Overall the early locomotion technique was likely generalized (Martin, 1972; Cartmill, 1972). Instead of being an ancestral state of locomotion vertical clinging and leaping likely evolved as several different lineages since they lack an overall anatomical feature and lack a similar feeding environment (Gebo, 2011).

Vertical clinging and leaping as an ancestral condition would not be possible since there is a lack of generalized morphology shared between haplorrhine and strepsirrhines vertical clingers and leapers. For example, the hind limb anatomies are different between differently sized species that practice vertical clinging and leaping and thus no overall anatomical pattern exists (Stern and Oxnard, 1973). Overall the early locomotion technique was likely generalized (Martin, 1972; Cartmill, 1972). Instead of being an ancestral state of locomotion vertical clinging and leaping likely evolved as several different lineages since they lack an overall anatomical feature and lack a similar feeding environment (Gebo, 2011).

Gorillas are found within Gabon, the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), the Republic of the Congo, Equatorial Guinea, the Central African Republic, Cameroon, Rwanda, and Uganda (Robbins et al., 2001). Gorillas are part of the taxonomic family of Pongidae (Great Apes). Groves (1970) split gorillas into three subspecies: western lowland gorilla (Gorilla gorilla gorilla), eastern lowland gorilla (Gorilla gorilla graueri) and mountain gorillas (Gorilla gorilla beringei).

Gorillas are found within Gabon, the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), the Republic of the Congo, Equatorial Guinea, the Central African Republic, Cameroon, Rwanda, and Uganda (Robbins et al., 2001). Gorillas are part of the taxonomic family of Pongidae (Great Apes). Groves (1970) split gorillas into three subspecies: western lowland gorilla (Gorilla gorilla gorilla), eastern lowland gorilla (Gorilla gorilla graueri) and mountain gorillas (Gorilla gorilla beringei). Although all of the gorilla’s subspecies are folivorious they exhibit differences in diet diversity (Taylor et al., 2003). Mountain gorillas tend to be more folivorious when compared to eastern and lowland gorillas. Western lowland gorillas tend to feed on fruits and insects along with leaves. Eastern lowland gorillas are seasonally frugivores (Yamagiwa et al., 1994; 1996; Kuroda et al., 1996; Robbins et al., 2001). Mountain gorillas lack fruit in their diet because of their high elevation locations. They tend to live at elevations of approximately 4000 meters (Robbins et al., 2001).

Although all of the gorilla’s subspecies are folivorious they exhibit differences in diet diversity (Taylor et al., 2003). Mountain gorillas tend to be more folivorious when compared to eastern and lowland gorillas. Western lowland gorillas tend to feed on fruits and insects along with leaves. Eastern lowland gorillas are seasonally frugivores (Yamagiwa et al., 1994; 1996; Kuroda et al., 1996; Robbins et al., 2001). Mountain gorillas lack fruit in their diet because of their high elevation locations. They tend to live at elevations of approximately 4000 meters (Robbins et al., 2001).

Western lowland gorillas are widely distributed and have a population of 110,000 gorillas (Robbins et al., 2001; Harcourt, 1996). They are located in Gabon, the DRC, the Central African Republic, the Republic of Congo, and Equatorial Guinea (Harcourt, 1996). Eastern lowland gorillas are mostly located in the DRC and have a population of 17,000 individuals (Harcourt, 1996; Robbins et al., 2001). Mountain Gorillas have two different geographic populations. The first population is located in the Virunga Mountains in Rwanda, Uganda and the DRC. The second population is located in Bwindi Impenetrable National Park in Uganda. They are made up of 600 individuals, 300 located in each area (Robbins et al., 2001).

Western lowland gorillas are widely distributed and have a population of 110,000 gorillas (Robbins et al., 2001; Harcourt, 1996). They are located in Gabon, the DRC, the Central African Republic, the Republic of Congo, and Equatorial Guinea (Harcourt, 1996). Eastern lowland gorillas are mostly located in the DRC and have a population of 17,000 individuals (Harcourt, 1996; Robbins et al., 2001). Mountain Gorillas have two different geographic populations. The first population is located in the Virunga Mountains in Rwanda, Uganda and the DRC. The second population is located in Bwindi Impenetrable National Park in Uganda. They are made up of 600 individuals, 300 located in each area (Robbins et al., 2001). The gorilla genus was fully recognized by Geoffrey in 1853 (Groves, 2001). Western gorillas (Gorilla gorilla gorilla) are documented as having relatively small teeth and larger incisors when compared with eastern gorillas. They also have shorter hair, brown gray to reddish crowns, flared nostrils, and adult males have a characteristic light gray back and thighs (Groves, 2001). Eastern gorillas (Gorilla beringei) are described as having small incisors when compared to western gorillas. They have longer hair specifically on their brows, tend to be jet black and exhibit gray white back only. They also have narrower nostrils. Mountain gorillas (Gorilla beringei beringei) are described as being quite large with a strongly flared jaw. They are shaggier and have angular nostrils (Groves, 2001).

The gorilla genus was fully recognized by Geoffrey in 1853 (Groves, 2001). Western gorillas (Gorilla gorilla gorilla) are documented as having relatively small teeth and larger incisors when compared with eastern gorillas. They also have shorter hair, brown gray to reddish crowns, flared nostrils, and adult males have a characteristic light gray back and thighs (Groves, 2001). Eastern gorillas (Gorilla beringei) are described as having small incisors when compared to western gorillas. They have longer hair specifically on their brows, tend to be jet black and exhibit gray white back only. They also have narrower nostrils. Mountain gorillas (Gorilla beringei beringei) are described as being quite large with a strongly flared jaw. They are shaggier and have angular nostrils (Groves, 2001). Gorillas live in polygynous cohesive groups that contain several females, their offspring and one or two males (Robbins et al., 2001). Gorillas also exhibit pronounce sexual dimorphism with males being nearly twice the size of the females. Mountain gorillas exhibit the largest degree of sexual dimorphism (Stewart and Harcourt, 1987) Sexual dimorphism suggests severe competition between males for females (Robbins et al., 2001). However, some males will be unable to attract females. They will likely have lower reproduction outputs when compared to dominant males (Harcourt, 1987; Robbins et al., 2001).

Gorillas live in polygynous cohesive groups that contain several females, their offspring and one or two males (Robbins et al., 2001). Gorillas also exhibit pronounce sexual dimorphism with males being nearly twice the size of the females. Mountain gorillas exhibit the largest degree of sexual dimorphism (Stewart and Harcourt, 1987) Sexual dimorphism suggests severe competition between males for females (Robbins et al., 2001). However, some males will be unable to attract females. They will likely have lower reproduction outputs when compared to dominant males (Harcourt, 1987; Robbins et al., 2001). Females generally exhibit natal dispersal as a mechanism to avoid inbreeding (Stewart and Harcourt, 1987). Young adult males will often be at the peripheries and will emigrate out of their natal group. Following their emigration, they will likely be solitary or join a group of bachelor males prior to attempting to take over a group of females (Stewart and Harcourt, 1987). Females generally give birth to their first infant at 10 years of age. Generally, they exhibit a birth ratio of 3.92. When they have infants, females tend to spend more time with the dominant male (Robbins et al., 2001).

Females generally exhibit natal dispersal as a mechanism to avoid inbreeding (Stewart and Harcourt, 1987). Young adult males will often be at the peripheries and will emigrate out of their natal group. Following their emigration, they will likely be solitary or join a group of bachelor males prior to attempting to take over a group of females (Stewart and Harcourt, 1987). Females generally give birth to their first infant at 10 years of age. Generally, they exhibit a birth ratio of 3.92. When they have infants, females tend to spend more time with the dominant male (Robbins et al., 2001). Gorillas (eastern and western lowland gorillas) are sympatric with chimpanzees due to their reliance on fruit (Robbins et al., 2001). Mountain gorilla’s territories do not overlap with chimpanzees. The main predators of gorillas are leopards (Panthera pardus) (Fay et al., 1995). Fay et al, (1995) documented an adult male gorilla remains being found on a leopard’s face.

Gorillas (eastern and western lowland gorillas) are sympatric with chimpanzees due to their reliance on fruit (Robbins et al., 2001). Mountain gorilla’s territories do not overlap with chimpanzees. The main predators of gorillas are leopards (Panthera pardus) (Fay et al., 1995). Fay et al, (1995) documented an adult male gorilla remains being found on a leopard’s face.

female dominance, which is defined as the ability of females to consistently evoke submissive behavior from all males (Jolly, 1966; Richard, 1987; Kappeler, 1993). Female dominance can only occur in contexts of male submission (Hrdy, 1981). When males exhibit spontaneous male submission to females in the absence of female aggression, this is termed deference (Kappeler, 1993a). In the absence of male deferential behavior, females can elicit submissive male behavior through the use of aggression (Sauther, 1993).

female dominance, which is defined as the ability of females to consistently evoke submissive behavior from all males (Jolly, 1966; Richard, 1987; Kappeler, 1993). Female dominance can only occur in contexts of male submission (Hrdy, 1981). When males exhibit spontaneous male submission to females in the absence of female aggression, this is termed deference (Kappeler, 1993a). In the absence of male deferential behavior, females can elicit submissive male behavior through the use of aggression (Sauther, 1993). Another animal that has shown female dominance is the spotted hyena (Kruuk, 1972; Frank, 1989; Smale et al., 1993). However, they do not exhibit true female dominance, as seen in lemurs, since female hyenas do not consistently dominate males in all contexts (Smale et al., 1993; Frank et al., 1989). Jolly (1966) found most dominance interactions that occur among lemurs occur in the context of feeding and often occur with the female supplanting the males. Female lemurs will have feeding priority after winning aggressive interactions with males who submissively vocalize and retreat (Jolly, 1966, 1967, 1984).

Another animal that has shown female dominance is the spotted hyena (Kruuk, 1972; Frank, 1989; Smale et al., 1993). However, they do not exhibit true female dominance, as seen in lemurs, since female hyenas do not consistently dominate males in all contexts (Smale et al., 1993; Frank et al., 1989). Jolly (1966) found most dominance interactions that occur among lemurs occur in the context of feeding and often occur with the female supplanting the males. Female lemurs will have feeding priority after winning aggressive interactions with males who submissively vocalize and retreat (Jolly, 1966, 1967, 1984). energy and maximize scare resources, and suggested three hypotheses to explain the evolution of female dominance in lemurs. The energy conservation hypothesis emphasizes the harsh island climate that selected for female dominance. The evolutionary disequilibrium hypothesis suggests that lemur traits are the result of a transition from nocturnal lifestyle to a more diurnal lifestyle. The energy frugality hypothesis predicts that certain lemur traits developed for maximization of food resources and thus to conserve energy (Wright, 1999). Wright (1999) suggested that the harsh and unpredictable island environment ofMadagascar led to the evolution of several behavioral characteristics, including female dominance, targeted female to female aggression, high female mortality rate, strict seasonal breeding and weaning synchrony.

energy and maximize scare resources, and suggested three hypotheses to explain the evolution of female dominance in lemurs. The energy conservation hypothesis emphasizes the harsh island climate that selected for female dominance. The evolutionary disequilibrium hypothesis suggests that lemur traits are the result of a transition from nocturnal lifestyle to a more diurnal lifestyle. The energy frugality hypothesis predicts that certain lemur traits developed for maximization of food resources and thus to conserve energy (Wright, 1999). Wright (1999) suggested that the harsh and unpredictable island environment ofMadagascar led to the evolution of several behavioral characteristics, including female dominance, targeted female to female aggression, high female mortality rate, strict seasonal breeding and weaning synchrony. Richard (1987) argued that females have a strong interest in maintaining their position of social dominance in order to maintain their priority access to food. Males will accept female dominance in order to further their reproductive interests through promoting the survival of their unborn young. Hrdy (1981) argues that the females’ reproductive success is dependent on the ability to obtain resources, and thus that the social dominance of female lemurs and male deference to females is necessary in order to conserve energy for the brief and annual mating season. Jolly (1984) suggested that female dominance occurred due to seasonal stressors on the females.

Richard (1987) argued that females have a strong interest in maintaining their position of social dominance in order to maintain their priority access to food. Males will accept female dominance in order to further their reproductive interests through promoting the survival of their unborn young. Hrdy (1981) argues that the females’ reproductive success is dependent on the ability to obtain resources, and thus that the social dominance of female lemurs and male deference to females is necessary in order to conserve energy for the brief and annual mating season. Jolly (1984) suggested that female dominance occurred due to seasonal stressors on the females. Sauther (1993) in her study of ring-tailed lemurs in Beza Mahafaly, Madagascar found that her data supported female dominance as a response to the high reproductive costs experienced by female lemurs in the seasonal and harsh environment of Madagascar. Sauther (1993) suggested that males are both direct and indirect feeding competitors of females, and that this competition often coincides with periods of high-cost reproductive states, including lactation during periods of low food availability.

Sauther (1993) in her study of ring-tailed lemurs in Beza Mahafaly, Madagascar found that her data supported female dominance as a response to the high reproductive costs experienced by female lemurs in the seasonal and harsh environment of Madagascar. Sauther (1993) suggested that males are both direct and indirect feeding competitors of females, and that this competition often coincides with periods of high-cost reproductive states, including lactation during periods of low food availability.

Female dominace is exhibited by most lemur species and involves the ability for the female to consistently evoke submissive behavior from all males (Jolly, 1966; Richard, 1987; Kappeler, 1993). emale dominance can only occur in contexts of male submission (Hrdy, 1981). When males exhibit spontaneous male submission to females in the absence of female aggression, this is termed deference (Kappeler, 1993a). In the absence of male deferential behavior, females can elicit submissive male behavior through the use of aggression (Sauther, 1993).

Female dominace is exhibited by most lemur species and involves the ability for the female to consistently evoke submissive behavior from all males (Jolly, 1966; Richard, 1987; Kappeler, 1993). emale dominance can only occur in contexts of male submission (Hrdy, 1981). When males exhibit spontaneous male submission to females in the absence of female aggression, this is termed deference (Kappeler, 1993a). In the absence of male deferential behavior, females can elicit submissive male behavior through the use of aggression (Sauther, 1993). Another animal that has shown female dominance is the spotted hyena (Kruuk, 1972; Frank, 1989; Smale et al., 1993). However, they do not exhibit true female dominance, as seen in lemurs, since female hyenas do not consistently dominate males in all contexts (Smale et al., 1993; Frank et al., 1989). Jolly (1966) found most dominance interactions that occur among lemurs occur in the context of feeding and often occur with the female supplanting the males. Female lemurs will have feeding priority after winning aggressive interactions with males who submissively vocalize and retreat (Jolly, 1966, 1967, 1984).Ring-tail lemurs lack sexual dimorphism, both females and males are the same size (Mittermeier et al., 1994; Sussman, 2000).

Another animal that has shown female dominance is the spotted hyena (Kruuk, 1972; Frank, 1989; Smale et al., 1993). However, they do not exhibit true female dominance, as seen in lemurs, since female hyenas do not consistently dominate males in all contexts (Smale et al., 1993; Frank et al., 1989). Jolly (1966) found most dominance interactions that occur among lemurs occur in the context of feeding and often occur with the female supplanting the males. Female lemurs will have feeding priority after winning aggressive interactions with males who submissively vocalize and retreat (Jolly, 1966, 1967, 1984).Ring-tail lemurs lack sexual dimorphism, both females and males are the same size (Mittermeier et al., 1994; Sussman, 2000).

catta are endemic to southwestern Madagascar (Sussman, 1977). Madagascar is located 800 kilometers from Southeast Africa. It is the fourth largest island in the world (Swindler, 2002). Southern Madagascar is characterized by a rainy season that occurs from November to March (Jolly, 1966). L. catta are mainly found in forests of dry bush, gallery, deciduous, scrub and closed canopy forests (Mittermeier et al., 1994). L. catta are opportunistic omnivores and their diet mainly consists of fruit, leaves, flowers, herbs, other plant parts, and sap (Sauther, 1992; Mittermeier et al., 1994). Sauther (1992) found that 30% to 60% of their diet consisted of feeding on fruit and 30% to 51% of their diet consisted on feeding on leaves and herbs.

catta are endemic to southwestern Madagascar (Sussman, 1977). Madagascar is located 800 kilometers from Southeast Africa. It is the fourth largest island in the world (Swindler, 2002). Southern Madagascar is characterized by a rainy season that occurs from November to March (Jolly, 1966). L. catta are mainly found in forests of dry bush, gallery, deciduous, scrub and closed canopy forests (Mittermeier et al., 1994). L. catta are opportunistic omnivores and their diet mainly consists of fruit, leaves, flowers, herbs, other plant parts, and sap (Sauther, 1992; Mittermeier et al., 1994). Sauther (1992) found that 30% to 60% of their diet consisted of feeding on fruit and 30% to 51% of their diet consisted on feeding on leaves and herbs. catta live in multi male, multi female groups ranging from nine to twenty two animals but on average have groups of fourteen animals (Sauther, 1991; Sussman, 1991). Females are philopatric and males disperse; dispersing males tend to enter new groups with one or two other males from their original groups (Sauther, 1991; Sussman, 1991). Generally one female is the single highest-ranking female. The highest-ranking female is typically the one to initiate group movement in a certain direction (Jolly, 1966; Sauther and Sussman, 1993). Females form a dominance hierarchy in which certain females will out rank other females depending on the matriline to which they belong; however, every female is more dominant than males. These dominance relations are reinforced by agonistic encounters (Jolly, 1966; Taylor and Sussman, 1985; Gould et al., 1999).

catta live in multi male, multi female groups ranging from nine to twenty two animals but on average have groups of fourteen animals (Sauther, 1991; Sussman, 1991). Females are philopatric and males disperse; dispersing males tend to enter new groups with one or two other males from their original groups (Sauther, 1991; Sussman, 1991). Generally one female is the single highest-ranking female. The highest-ranking female is typically the one to initiate group movement in a certain direction (Jolly, 1966; Sauther and Sussman, 1993). Females form a dominance hierarchy in which certain females will out rank other females depending on the matriline to which they belong; however, every female is more dominant than males. These dominance relations are reinforced by agonistic encounters (Jolly, 1966; Taylor and Sussman, 1985; Gould et al., 1999). Males within these social groups are peripheral; however, there are often one to three central/dominant males. The male hierarchy is often dependent on age (Sussman, 1992). Generally the central males are more fit than other males, while the lower ranking/peripheral males are older, recently transferred males as well as younger males that have yet to transfer (Sussman, 1991; 1992; Gould, 1996; Gould et al., 1999). The higher-ranking males often have more interactions with females and thus are more likely to mate, but lower-ranking males also mate (Sussman, 1991, 1992; Gould, 1994, 1996; Gould et al., 1999).

Males within these social groups are peripheral; however, there are often one to three central/dominant males. The male hierarchy is often dependent on age (Sussman, 1992). Generally the central males are more fit than other males, while the lower ranking/peripheral males are older, recently transferred males as well as younger males that have yet to transfer (Sussman, 1991; 1992; Gould, 1996; Gould et al., 1999). The higher-ranking males often have more interactions with females and thus are more likely to mate, but lower-ranking males also mate (Sussman, 1991, 1992; Gould, 1994, 1996; Gould et al., 1999). Females start reproducing when they are two or three years old and generally havean interbirth ratio of 2 to 3 years (Sauther, 1991). Mating activity in a group will normally last for two to three weeks per year (Sauther, 1991), however, each individual female will only be sexually receptive for one to two days per year (Van Horn and Resko, 1977; Sauther, 1991).

Females start reproducing when they are two or three years old and generally havean interbirth ratio of 2 to 3 years (Sauther, 1991). Mating activity in a group will normally last for two to three weeks per year (Sauther, 1991), however, each individual female will only be sexually receptive for one to two days per year (Van Horn and Resko, 1977; Sauther, 1991).